317

MU'AWIYA II., MERWAN, AND 'ABD AL-MELIK, CALIPHS.

REBELLION OF IBN AZ-ZUBEIR AND AL-MUKHTAR

64-73 A.H. / 683-692 A.D.

YEZID'S early death was a misfortune to the Umeiyad rule. He was succeeded by his son Mu'awiya II., a weak and sickly youth, who survived but three months. He had the support of all the Syrians except those of Keis, whose objection to him was that his mother and grandmother were of Kelb. His maternal granduncle, Ibn Bahdal, was ruler de facto, and the brother of the latter was governor of Kinnasrin, a province settled by Keis. Keis was, therefore, jealous of the large share of Kelb in the government. Anticipating his decease, Mu'awiya told the people from the pulpit that, like Abu Bekr, he would have appointed a successor, but there was none he saw of 'Omar's stamp; that like 'Omar he would have nominated electors, but neither so did he see any men fit for such a task; and accordingly that he left them to choose a successor for themselves. The short and feeble reign served but to relax the sinews of the Empire.

On his death, the Umeiyad counsels were divided, and various aspirants to the throne appeared. Ibn az-Zubeir, now the acknowledged Caliph at Mecca and Medina, succeeded during the next few months in being recognized ruler also over Egypt and the greater part of Syria. He was proclaimed in Al-Basra by a Temimite, and 'Obeidallah, who relied on the Azd and Bekr, was forced to flee. Al-Kufa also went over to Ibn az-Zubeir. Persia was in the hands of the Khawarij. Syria, and only part even of that, remained under the government of Damascus.

Had Ibn az-Zubeir left his sanctuary for Syria, there is

little doubt but that he would have succeeded, and the Caliphate might then have been established in his family.

Even at Damascus, there was a numerous party in his favour, and most of the strongholds in Syria and Mesopotamia sided with him. Ibn Bahdal alone and the Syrian army, now returning from Arabia, were staunch to the Umeiyad interest, and they were reinforced by Umeiyads driven out of Medina. Ad-Dahhak, governor of Damascus, temporised. The young Caliph had left no child, but there was a brother, a younger son of Yezid, named Khalid. The family favoured him; but the chief men of the Court felt that a stronger hand was needed, and they put forward Merwan. An Umeiyad, he came from another branch, but had rendered devoted service to 'Othman and to the dynasty at large.1

After much dissension, he was saluted Caliph, on condition that Khalid should succeed on reaching man's estate. Ad-Dahhak now showed his colours in the interest of Ibn az-Zubeir, and retired with his adherents to Merj Rahit, a meadow in the vicinity. Merwan, with a following of the Kelb of the Jordan province and the Ghassin, pitched at Al-Jabiya. A strong antagonism was growing up between the two Bedawi branches of the Arabs, the Yemeni or "southern," against the Beni Bekr and the "northern." The former, especially the Beni Kelb, from which the Caliphs had taken wives, were devoted to the Umeiyad house; the Beni

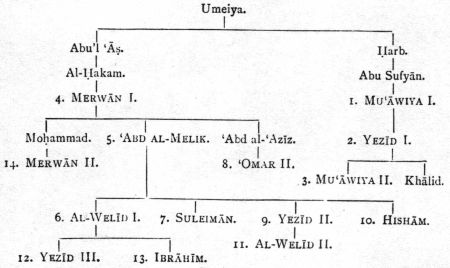

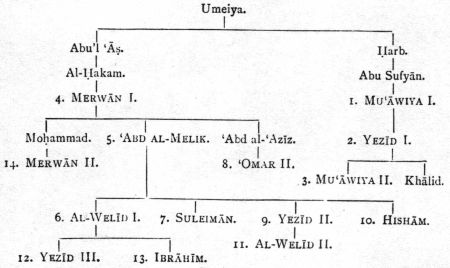

1 The subjoined tree will show the relationship of

the Umeiyad family:—

Keis and northern tribes were equally prejudiced against it, and joined Ad-Dahhak on the side of Ibn az-Zubeir.

Several months passed thus; at last, towards the close of the year, Merwan attacked his enemy at Merj Rahit, and after some weeks of fighting, completely discomfited him, Ad-Dahhak being left dead upon the field. Thereupon all Syria returned to its allegiance. Egypt also was regained; and an army under Mus'ab, brother of Ibn az-Zubeir, seeking to recover Syria, was put to flight. Merwan owed his success to two persons, 'Obeidallah the son of Ziyad, who persuaded him to contest the Caliphate when he and all the Umeiyads believed their case was hopeless, and Ibn Bahdal, who held sway over the Yemeni tribes. On his side fought besides Kelb and Ghassan, Sakun, Sahsak, Tanubh, Taj', and Kain. Ad-Dahhak was supported by Suleim, 'Amir (Hawazin), and Dhubyan—all Keis. The battle gave rise to a blood-feud between the Kelbi and Keisi tribes, traces of which exist down to the present day.

Allegiance had been sworn to Merwan on 3 xi. 64 A.H. (June 22, 684 A.D.) at Al-Jabiya, and after the battle the oath was renewed at Damascus, two months later; but in the midst of his success, he came to an ignoble and untimely end. Fearing the stability of his throne, he set aside the recognised arrangement by which Khalid, brother of the late Caliph, should succeed, in favour of his own son 'Abd al-Melik, whom he proclaimed heir-apparent. Then either with the view of reconciling Khalid's mother, that is, the widow of Yezid, or of weakening her son's claim, he took her himself to wife. Further, he made light of her son, and treated him with indignity. The proud Bedawi dame was offended and took a signal revenge. As the Caliph slept by her side, she smothered him with a pillow, so that he was found dead in his bed. Born at the beginning of the Muslim era, and now over threescore years of age, he had gained an unenviable notoriety as an unscrupulous agent of the faction of 'Othman, though his demerits have no doubt been magnified by the opposite party. His reign lasted barely a year.

He was succeeded his son 'Abd al-Melik, whose authority was at once recognised throughout Syria and Egypt.

It may be useful for a moment to notice events transpiring in the East which illustrate the intense jealousy

that reigned between the Southern and Northern divisions of the Arab race, often with serious injury to the State.

About this time, the rivalry broke out in Persia into fierce internecine warfare. For a whole year, Ibn Khazim of Suleim, ibn az-Zubeir's governor in Khorasan, fought on the part of the Modar (or "northern") branch against Bekr (allied to "southern"), and in a victory gained at Herat slew 8000 of his foes. His son having been killed by a party of the Temim tribe commanded by Al-Horeish, fighting was kept up for two years.

In the following year, Ibn Khazim, still seeking to avenge his son's blood, stormed a fortress in which some eighty of the Beni Bekr had taken refuge. Marvellous tales are related of the feats and prowess of the little band; but their end was to be starved to death. Their chivalry has been handed down in verses by Al-Horeish, which are still preserved.

Such are the scenes over which, both in prose and verse, the Arab loves to dwell; and too much prominence may perchance have been given to them by our annalists. But the tribal jealousies and bloody engagements long prevailing amongst the Arab bands in Khorasan and Eastern Persia, serve no doubt to explain why for many years there was so little progress made in the settlement of that territory, and in the extension of the frontier to the North and East.

Meantime Keis still held its ground on the Euphrates, and on the restoration of peace in Syria, Merwan had despatched an army under 'Obeidallab to reoccupy Mesopotamia from Mosul downwards, and thereafter advance on Al-Kufa. A second, intended to recover Medina, was routed on its way by the troops of Ibn az-Zubeir, whose supremacy continued to be recognised throughout Arabia, Al-'Irak, and the East His brave brother Mus'ab continued governor of al-Basra, though exposed there to serious jeopardy from the Khawarij. These at the first rallied round Ibn az-Zubeir in defence of Mecca against the army of Yezid. But on his laying claim to the Caliphate, they demanded that he should join with them not only in condemning the "murderers" of al-Hosein, but also in denouncing 'Othman as a tyrant justly put to death. This he could not do without compromising his whole career; for, in company with his father Az-Zubeir, he had waged war with 'Ali for the avowed purpose of avenging

the blood of that unfortunate Caliph. The theocrats, incensed at his refusal, now turned against Ibn az-Zubeir, whose brother Mus'ab had hard work in opposing them.

Over and over again they got possession of Al-Basra, and when at last, driven out they retired to Al-Ahwaz and spread themselves over Persia. There committing continual ravages under one name or another (for they split up into many sects), they were with difficulty held in check by Al-Muhallab, a brave general who had already distinguished himself in Khorasan, and was now summoned for this task by Mus'ab.

Meanwhile an adventurer of a very different type, Al-Mukhtar, came on the scene at Al-Kufa. He was son of the Abu 'Obeid slain in the battle of the Bridge, and belonged to the notorious tribe of Thakif. Designing and unprincipled, Al-Mukhtar was ever ready to take the side most for his own advantage. He was one of those who pursued Al-Hasan when, as Caliph, he fled from Al-Kufa to Al-Medain and, on the other hand, he took part with Muslim, when deputed by Al-Hosein to Al-Kufa. On the last occasion, he was seized by 'Obeidallah, then governor of the city, who struck him a blow that cost him an eye. Escaping to Arabia, he swore that he would revenge the injury by cutting the tyrant's body into a thousand pieces. At Mecca he aided Ibn az-Zubeir in opposing the Syrian attack on the Holy City; but distrusted by him, he departed and set up on his own account.

Towards the close of 64 A.H. he returned to Al-Kufa, now under one of Ibn az-Zubeir's lieutenants, and gained a name by joining in the cry of vengeance, raised by the 'Alid party, against all who had been concerned in the attack upon Al-Hosein. But, suspected by the governor of sinister designs, he was seized and cast into prison.

The civil war which now broke out was in reality a rising of the Persian Mawali against their Arab masters, but it was given a religious colouring. For, about this time, a wild fanaticism had seized the Khawarij of Al-Kufa, to revenge the death of Al-Hosein. Ever since the tragedy at Kerbala, a party there had more or less conspired to slay all those who had joined the enemies of their Prophet's grandson. The feeling now became intense.

Early in 65 A.H., numbers of "the Penitents" (Tauwabin), as they called themselves, visited the tomb of Al-Hosein at Kerbala,

and gathering there "in a throng thicker than the throng that gathers around the Ka'ba," raised a bitter cry, and spent the night in a loud wail of self-reproach for having deserted in his extremity the son of Fatima and 'Ali. Then they set out to attack the godless Syrians.

Met near Kirkisiya by the Caliph's troops, they fought with desperate bravery, but were utterly defeated, their leaders slain, and the remnant driven back to Al-Kufa.1

Al-Mukhtar from his prison sent to the defeated "Penitents" a fulsome panegyric with hopes of future victory. Having obtained his liberty, he set up as the professed delegate of Mohammad, Ibn al-Hanefiya, to execute vengeance on the enemies of his father's house. By dint of specious assertions, forged letters, and a certain countenance from Mohammad himself, then at Medina, he gained over Ibrahim ibn al-Ashtar2 and other influential men of Al-Kufa. By their aid he expelled the governor of Ibn az-Zubier, gained possession of the city, and succeeded in extending his sway over Al-'Irak and even parts of Persia and Arabia.

His first great effort was directed against his old enemy 'Obeidallah, who during the past year had been endeavoring to reduce the power of Ibn az-Zubeir in Mesopotamia, and now threatened Mosul. For this end Al-Mukhtar despatched Ibn al-Ashtar with an army; but no sooner had it left Al-Kufa, than the citizens, many of whom had no sympathy with the 'Alid movement, and were indeed themselves

amongst the "murderers" of Al-Hosein, rose in rebellion against Al-Mukhtar. He hastily recalled Ibn al-Ashtar for his defence. A terrible conflict ensued in the streets of Al-Kufa, tribe against tribe, the Yemen against Keis, faction against faction, till the cry on one side "Down with the murderers of Al-Hosein!" on the other "Down with the murderers of 'Othman!" resounded throughout the city. At last, after some 800 had been slain, Al-Mukhtar's party

1 The wild fanaticism of these people is illustrated by

the war-cry of one who thus exhorted his fellows: "Whoso desireth the life after which

there is no death, the journey after which there is no weariness, the joy after which there

is no grief, let him draw nigh unto his Lord in this battle, and breathe out his soul in Paradise."

2 Son of the Al-Ashtar who bore so prominent a part

on 'Ali's side in the battle of Siffin.

gained the victory. An amnesty was called; but from it all who had taken part against Al-Hosein were shut out.

These including,—besides Shamir, 'Omar, and other leading actors in the tragedy,—no fewer than 284 citizens of lesser note, were ruthlessly put to death. And so Al-Mukhtar at once achieved the ostensible object of his mission, and avenged himself by horrid cruelties upon his enemies.1 The heads of 'Omar and his son, slain after he had given them quarter, were sent to Mohammad Ibn al-Hanefiya, with this message,—"I have destroyed every man within my reach concerned in the attack upon Al-Hosein, thy martyred brother; and I will yet slay the remainder, if the Lord will." Only a few escaped to Al-Basra.

While émeute and slaughter were thus going on, 'Obeidallah had taken Mosul, and was advancing on Al-'Irak. Al-Mukhtar, now that he was rid of his foes at home, hurried off the army under Ibn al-Ashtar to meet his arch-enemy. He himself accompanied it a short way, when a scene, worthy of the unprincipled pretender, was enacted to stir the fanatic zeal of the troops. A party of his followers drew near with a worn-out chair borne upon a mule. "The chair of 'Ali!" cried Al-Mukhtar; "a messenger from heaven2 sent to slay thousands upon thousands of the wicked ones; even as the ark brought victory unto the children of Israel!" "Nay!" cried the pious Ibn al-Ashtar, as the crowds with uplifted arms shouted around the chair—"Call it rather the golden calf which led the Israelites astray." The wretched scandal thus countenanced by Al-Mukhtar tended to lower him in the eyes of all the thinking citizens. Meanwhile, with an immense force, 'Obeidallah was advancing from Mosul, and the Kufan army hurried on to anticipate him before he should invade Al-'Irak.

The two armies met on the banks of the Zab at the beginning of the year 67 A.H. But there

1 "Some they stoned, some they stabbed, and some

they shot with arrows like as they had shot Al-Hosein." Of one, Al-Mukhtar had the

four limbs cut off, and the wretched creature so left to die; another half dead, they burned

in the fire. The feeling ran so high as to override the ties of nature; thus the citizen who

brought in from Kerbala the head of Al-Hosein was hunted down till at last he was pointed

out by the fanatic piety of his own wife, and slain.

2 Quoting the Kor'an, Sura lxxvii. 1.

was treachery in the Syrian camp. The Beni Keis had not forgotten the field of Merj Rahit, and they carried the left wing in a body over to the enemy. Beaten at first by the other wing, Ibn al-Ashtar recovered his position; and in a furious charge, nerved by the cry of "vengeance on the tyrant 'Obeidallah and the murderers of Al-Hosein!" routed the Syrian force, of which the most that escaped the sword perished in the swift waters of the Zab.

'Obeidallah and Hosein ibn Numeir were among the slain. The head of 'Obeidallah was carried to Al-Kufa, and cast before Al-Mukhtar on the very spot where, six years before, as governor of Al-Kufa he had so roughly handled the gory head of the Prophet's grandson.1 Thus early was the tragedy of Kerbala avenged in the blood of its chief actor, and of almost all who had taken part in it.

The victory of Ibn al-Ashtar revived the hopes of the Keis tribes; it also made Al-Mukhtar for the moment undisputed master of Mesopotamia. His fortune, however, built up on a sand-bed of false pretences, was but of short duration. He tried to hold with Ibn az-Zubeir; but Ibn az-Zubeir had no faith in him; and to test his profession of loyalty summoned him to Mecca. Al-Mukhtar, refusing, assumed a hostile attitude, and sent a force to succor Ibn al-Hanefiya, whose life Ibn az-Zubeir had threatened unless he would do him homage.2 He also despatched an army to Medina with the ostensible object of defending it from Syrian attack; but Ibn az-Zubeir, divining his ambitious designs, sent a force in the same direction which cut it to pieces.

Mus'ab, brother of Ibn az-Zubeir, was still governor of Al-Basra. Fortunately for 'Abd al-Melik his hands were full. The Kufans who had escaped thither from the tyranny of Al-Mukhtar, now besought Mus'ab to rid them of their adversary. Nothing loth, he summoned the brave Muhallab from Fars, where he was still fighting against the against the Khawarij and, thus supported, some little time after the battle of the

1 The feeling of abhorrence towards 'Obeidallah may

be gathered from the tradition that a viper issued from his head and kept crawling from

his mouth into his nose, and so backwards and forwards.

2 Eventually Ibn al-Hanefiya tendered allegiance to

'Abd al-Melik, and we hear little more of him.

Zab, Mus'ab set out for Al-Kufa with a fully equipped army. He was met on the way by the troops of Al-Mukhtar, whom he totally discomfited. Al-Mukhtar then rallied his adherents in Al-Kufa, and himself at their head encountered the enemy just outside the walls; but he was driven back, and with some 8000 followers, mostly Persians, forced to take refuge in the Fort. For several months they held out, but with little sympathy from the citizens at large. At last, driven by hunger and thirst, Al-Mukhtar called on the garrison to go forth with him and fight either for victory or a hero's death.

He was followed but by nineteen, and with them met his fate. The rest surrendered at discretion. There was much discussion as to whether these should be spared, or at least those amongst them of Arab blood, who numbered 700.1 But the army was incensed, and the citizens of Al-Kufa had no favour for them; and so Mus'ab gave command, and the whole seven or eight thousand were beheaded. It was a deed of enormous ferocity, and brought Mus'ab into well-merited disfavour with his brother Ibn az-Zubeir. The hand of the pretender was nailed to the wall of the Mosque, where it remained till taken down by Al-Hajjaj; and the cruelties were crowned by putting to death one of the widows of Al-Mukhtar, who refused to speak otherwise than well of her husband's memory.2 Thus ended the short-lived triumph of Al-Mukhtar, but a year and a half after his seizure of the city. The cause which he championed—that of the Mawali—seemed lost, but the fire quenched in blood in Al-Kufa, where the Arabs were strong, broke out again in Khorasan sixty years later; and this time it was not put out.

During the next two years there was little change in the relations subsisting between the several provinces. 'Abd al-Melik looked quietly on while Mus'ab made an end of Al-Mukhtar. The Khawarij kept the East in constant alarm. They scoured the country, made cruel

1 It is instructive to observe the distinctive value

at this period placed on the life of Arabs, when it was calmly proposed to set the Arab

prisoners free and slay the "clients" of foreign blood.

2 Elegies by different poets mark the horror at

this atrocious act.

attacks on the unoffending people,1 took Ar-Reiy, besieged Ispahan for months, overran Al-Ahwaz and Kirman, and even threatened Al-Kufa. Al-Muhallab, the only general able to cope with these savage fanatics, had been unwisely withdrawn from the field for the government of Mosul. Mus'ab now again sent him against the Khariji bands; and after eight months of unceasing warfare he succeeded in dispersing them for the time.

The temporary quiet which apart from these Khariji outrages, at this period prevailed throughout the Empire is signalised by the singular spectacle chronicled by tradition, that whereas the Meccan solemnities were always headed by the Sovereign himself or by his Lieutenant, there were in the year 68 A.H., four leaders who, without any breach of harmony, presided at the Pilgrimage, each over his own adherents,—namely Ibn az-Zubeir, Ibn al-Hanefiya, the Khariji Najda, who held the south of Arabia, and the representative of the Umeiyads. Yet no act of violence took place.

Now that the power of Al-Mukhtar and of the Khawarij had been broken for him, 'Abd al-Melik had for some time been contemplating operations against Ibn az-Zubeir, and had in fact started on more than one occasion for a campaign to commence in the north of Syria, and sweep down upon Al-'Irak and Arabia; but a severe famine paralysed his efforts for a time. At last, in the summer of 689 A.D. (69-70 A.H.) he set out against the Keis in Kirkisiya, but was recalled by a danger which threatened his throne and led to an act which has left an indelible stigma on his name. At the time of Merwan's accession, it was stipulated that the minor son of Yezid should have the next claim. A similar expectation was held out, either then or afterwards to 'Amr ibn Sai'd, cousin of the Caliph and governor of Damascus. Both expectations were defeated by the succession of 'Abd al-Melik, and the injury rankled in the mind of 'Amr ibn Sa'id. Accordingly, on the Caliph's camp nearing Aleppo, he left it secretly by night, re-entered Damascus, and set up for himself as Caliph. 'Abd al-Melik

1 These theocratic fanatics seem throughout

to have had a strange fascination for the most savage creuelties, regarding them

apparently as service to God, if only perpetrated against those held by them as

heretics. They even cut up women big with child.

hurried back, and after some inconclusive engagements offered an amnesty, on which the fighting ceased, and a deed of pardon was given to 'Amr.

A few days after, the Caliph, who had resolved on his death, summoned him to his presence. He went against the advice of his friends, clad in armour below his dress, and with a large following, which, however, were shut out at the palace gates. Accosting him in friendly accents 'Abd al-Melik bade him sit down by him, and after indifferent conversation, signified that he wished to fulfil an oath he made on first hearing of 'Amr's rebellion, namely, that he would bind him hand and foot; but that having fulfilled his oath he would afterwards unloose him. 'Amr submitted, but no sooner was he bound than the Caliph smote him violently, and having bid his brother 'Abd al-'Aziz put him to death, went forth to evening prayers. Returning shortly, he was startled to find his victim still alive and, taunting his brother, who said he had not the heart to do the deed, with cowardice, himself stabbed 'Amr to death, and then cast his head with a heavy largess to the crowd without. 'Amr's followers were put to flight; his sons and adherents, with difficulty spared, were banished, and peace restored. The Caliph then sent to the widow for the deed of amnesty;—"It is in the grave with my husband," she replied, "that he may arraign thee before his Lord thereby." 'Abd al-Melik was not otherwise a cruel or hard-hearted man; but this act of refined and ruthless treachery created a widespread impression against him at the moment.1

Secure in Syria, 'Abd al-Melik, apparently for the third time, renewed his design against Ibn az-Zubeir and Mus'ab. There was a strong party in the Caliph's favour at Al-Basra; but endeavour through an emissary to stir them into active loyalty having failed, the Caliph resolved himself to head a force for Mesopotamia and Al-'Irak. The Greeks, taking

1 For example, it alarmed Ibn al-Hanefiya, and

prevented his coming in for a time. The Caliph is represented as rather boasting

of it at Al-Kufa: "Beware," he said, "for I have the bonds by me which I cast around

the neck of 'Amr ibn Sa'id." According to some accounts 'Amr's rebellion took place

somewhat later, on the occasion of the Caliph's setting out for Al-'Irak against Mus'ab;

but the main outlines otherwise are the same; 'Amr persisting in his claim, the Caliph

felt that his life was not safe, and that either he or 'Amr must die.

advantage of the divisions in the Muslim Empire, pressed heavily at this time on the Syrian frontier; and 'Abd al Melik, to be free for his enterprise, had to make a truce with them at the weekly tribute of 1000 golden pieces. It was the year 71 A.H. before 'Abd al-Melik again broke ground. Having sown disaffection widely in Al-Kufa and Al-Basra by missives promising pardon and rewards, he laid siege to Kirkisiya, where Ibn az-Zubeir's governor ere long accepted the offer of amnesty, and with the Keis tribes joined the Caliph's army. Mus'ab, now thoroughly alarmed, sought the help of Al-Muhallab, but that general was at the moment hotly engaged with the Khawarij, who were close upon the walls of Al-Basra. So he had to meet the Caliph on the Syrian frontier with only Ibn al-Ashtar, who, though tempted with the promise of Al-'Irak, stood fast by Mus'ab. When the two armies met, it was soon seen that the Caliph's missives had taken effect, and that treachery was rife in Mus'ab's camp.

Ibn al-Ashtar, the only loyal friend he had, was one of the first to fall; and Mus'ab, deserted by his troops, and having seen his son slain before his own eyes, refusing quarter, was slain by one of his Kufaites, a hero to the last. His head, with the nose cut off; was sent round by 'Abd al-Melik to Egypt and Damascus. It was then to have been shown over the cities of Syria, when the Caliph's wife, with better feeling, had it washed and buried. Mus'ab died aged thirty-six. He was handsome and brave; but his memory is stained by the butchery perpetrated by his command at the death of Al-Mukhtar.

On Mus'ab's death, the Kufan army swore allegiance to 'Abd al-Melik, as did also

the Arab tribes of the Syrian desert. Advancing on Al-Kufa, he encamped by the

city forty days. There, one of the citizens made him a great feast at the ancient palace

of the Khawarnak,1 open to all.

'Abd al-Melik was delighted:—"If it would only last!" he said, "but as the poet

sang" (and he quoted some verses), "all is transitory here." Then he was

taken over the palace, and being told of the ancient princes of Al-Hira who lived there,

extemporised a couplet (for he was himself a poet),

1 For the Palace of the Khawarnak,

see Life of Mahomet, 1st edition, vol. i. p. clxxi.

signifying that the world passes away, and but repeats itself.1 The Caliph was fortunate in obtaining the adhesion of Al-Muhallab, whom he confirmed in his commission against the Khawarij; and having arranged for the administration of Al-Basra, and the various Eastern posts, returned to Damascus.

Ibn az-Zubeir in retirement still held to his claim to the Caliphate. Virtual ruler for several years of the greater part of the Empire, he had remained singularly inactive at Mecca. His chief domestic work had been the restoration of the Holy House, destroyed 64 A.H. Having removed the débris, he came upon remains of the ancient limits of the Ishmaelite structure, and enlarged the walls accordingly.2 Fire, we are told, flashed from the sacred rock when Ibn az-Zubeir had the temerity to strike the foundation with his pickaxe, as the same terror had overawed the people sixty years before when, in the youth of the Prophet, the Ka'ba was dismantled and rebuilt.3 If instead of remaining inactive at home, and contenting himself with the issue of orders from the Holy City, he had gone forth to head his armies, the Caliphate might have been established in his line. But the defeat of his brother Mus'ab came upon him as an unlooked-for and fatal blow. He mounted the pulpit when hearing of it, and harangued the people on the treachery of the men of Al-'Irak, and his readiness to die in defence of the Ka'ba. But trusting perhaps to the immunity of the Sanctuary, he took no further steps.

If such were his thoughts, they were in vain; for before leaving Al-Kufa, 'Abd al-Melik resolved on putting an end to the pretensions of his rival. He therefore sent a column of horse and foot under Al-Hajjaj, an able officer now

1 "Be not vexed with care, for thou too shalt pass away: 2 A tradition is quoted from 'Aisha of Mohammad

having told her that he would himself have restored the Ka'ba to its ancient wider

dimensions, but that the people having been so recently reclaimed from idolatry, he

feared the effect upon them of appearing to tamper with the sacred edifice. Al-Hajjaj

subsequently took the temple down and rebuilt it on its former lines.

3 Life of Mohammad, p.27 et. seq.

Therefore enjoy thyself, O man! whilst thou canst;

For that which was, shall not be again when it hath passed;

And that which shall be, only as what hath already been."

coming to the front. Marching from Al-Kufa, Al-Hajjaj reached At-Ta'if, four days east of Mecca, in the month of Sha'ban (Jan. 692 A.D.), without opposition, and forwarded letters of pardon to Ibn az-Zubeir if only he would submit. But Ibn az-Zubeir declined the offer. Frequent skirmishes took place on the plain of 'Arafat, in which Al-Hajjaj got the advantage. Al-Hajjaj then sought from the Caliph leave to besiege Mecca, and also reinforcements. He obtained both. Men remembered how shocked the same 'Abd al-Melik had been when, eight years before, Mecca was stormed by order of Yezid, and so they said the Caliph had gone back in his religion. But this was hardly fair to him; for so long as Ibn az-Zubeir remained rival Caliph in that otherwise secure sanctuary, the Empire could not be free from the danger of revolt.

It was close upon the month of Pilgrimage when Al-Hajjaj, strengthened by reinforcements from Medina, from which Ibn az-Zubeir's governor had just been expelled, invested the city and mounted catapults on the surrounding heights. As the engines opened with their shot, the heavens thundered (so tradition goes) and twelve of the Syrian army were struck by lightning; but next day when the storm returned, the impartial thunderbolts fell upon the men of Mecca, an incident from which Al-Hajjaj drew happy augury. During the days of Pilgrimage, the bombardment was at the intercession of 'Omar's son 'Abdallah held over, and the solemnities proper to the season partially performed. The siege was shortly turned into a strict blockade, and in a few months the inhabitants, suffering the extremities of want, began to desert in great numbers to the enemy. Even two of his own sons did so, on Ibn az-Zubeir's advice; but a third preferred to stay and share his father's fate. The siege had now lasted seven months, when Ibn az-Zubeir lost heart. He was tempted to give in; but he would first consult his mother Asma, daughter of Abu Bekr, now a hundred years of age. The scene is touching. With the ancient spirit of the Arab matron, she exhorted her son, if still conscious of the right, to die as a hero should. "That," said he, as he stooped to kiss her forehead, "is what I thought myself; but I wished to strengthen my thought by thine." And so, putting on his armour, he rushed into the thickest, and fell in the

unequal fight.

The heads of Ibn az-Zubeir and two of his leaders were exhibited at Medina, and thence sent on to Damascus. Al-Hajjaj, giving thus early proof of his hard and cruel nature, had the pretender's body impaled on the outskirts of the Holy City. 'Abd al-Melik blamed him for his inhumanity, and bade him give the body up to Asma, by whose loving hands it was washed and committed to the grave.

Thus ended the rule of Ibn az-Zubeir, a man of noble but inactive spirit, who for nine years held the title, and much also of the real power, of Caliph. He died aged seventy-two.

His mother, Asma, is the same who, at the Hijra, seventy-three years before, tore off her girdle to bind with it the Prophet's wallet to his camel as he took his flight from the cave of Mount Thaur, and thus earned the historic name of "She of the shreds."1 It is one of the last links that connect the Prophet with the chequered days on which we have now entered. What a world of events had transpired within the lifetime of this lady!

The only one of Ibn az-Zubeir's governors who remained faithful to his memory was Ibn Khazim, now fighting with the rival clans of Khorasan. 'Abd al-Melik offered, if he swore allegiance, to confirm him in Khorasan; but he indignantly rejected the offer. "I would have slain the envoy," he said, "had he not been of my own Keis blood." But he made him swallow the Caliph's letter. Thereupon 'Abd al-Melik sent him the head of Ibn az-Zubeir, in order to assure him of his end. Ibn Khazim embalmed the relic, and forwarded it to the family of the deceased. He was shortly after slain in battle by one whose brother he had put to death in the intertribal warfare.

1 Life of Mohammad p. 140 f.

The Caliphate: Its Rise, Decline, and Fall [Table of Contents]

Answering Islam Home Page