|

THE DIFFERENT ARABIC VERSIONS OF THE

QUR'AN

Part 2: The Current Situation

By Samuel Green

|

Many Muslims have told me that all

Qur'ans in the world are exactly the same, and that it is perfectly preserved and free from any

variation. This idea is often said as a way of showing that the Qur'an is

superior to the Bible. Muslims says this because this is what their leaders teach them

about the Qur'an and the Bible. Consider the following Islam teaching.

No other book in the world can match the Qur'an ...

The astonishing fact about this book of ALLAH is

that it has remained unchanged, even to a dot,

over the last fourteen hundred years. ... No

variation of text can be found in it. You can

check this for yourself by listening to the

recitation of Muslims from different parts of

the world. (Basic Principles of Islam, p. 4)

No other book in the world can match the Qur'an ...

The astonishing fact about this book of ALLAH is

that it has remained unchanged, even to a dot,

over the last fourteen hundred years. ... No

variation of text can be found in it. You can

check this for yourself by listening to the

recitation of Muslims from different parts of

the world. (Basic Principles of Islam, p. 4)

The above claim is that all Qur'ans around the world are

identical and that "no variation of text can be found".

In fact the author issues a challenge saying, "You can

check this for yourself by listening to the

recitation of Muslims from different parts of

the world". In this article I will take up this

challenge to see if all Qur'ans are the same.

Contents

- Some history related to the recitation of the Qur'an.

- Compare two Arabic Qur'ans from

different parts of the world.

- The extent to which the differences affect the meaning.

- Appendix 1 - Muslim attitudes to the different versions.

- Appendix 2 - Why are there so many versions of the Quran?

- Appendix 3 - The Memorisation of the Quran

1. HISTORY

To start our investigation we turn to an Islamic Encyclopedia

written by a practicing Muslim. This scholar explains an important aspect

of the history of the Qur'an. Please read this quote a few times if you

are new to this area of study.

(C)ertain variant readings (of the Qur'an) existed and, indeed, persisted

and increased as the Companions who had memorised the text died,

and because the inchoate (basic) Arabic script, lacking vowel signs

and even necessary diacriticals to distinguish between

certain consonants, was inadequate. ...

In the 4th Islamic century, it was decided to have

recourse (to return) to "readings" (qira'at) handed down from

seven authoritative "readers" (qurra'); in order,

moreover, to ensure accuracy of transmission, two

"transmitters" (rawi, pl. ruwah) were accorded

to each. There resulted from this seven basic texts

(al-qira'at as-sab', "the seven readings"), each having

two transmitted versions (riwayatan) with only

minor variations in phrasing, but all containing meticulous

vowel-points and other necessary diacritical marks. ...

The authoritative "readers" are:

Nafi` (from Medina; d. 169/785)

Ibn Kathir (from Mecca; d. 119/737)

Abu `Amr al-`Ala' (from Damascus; d. 153/770)

Ibn `Amir (from Basra; d. 118/736)

Hamzah (from Kufah; d. 156/772)

al-Qisa'i (from Kufah; d. 189/804)

Abu Bakr `Asim (from Kufah; d. 158/778)

(Cyril Glassé, The Concise Encyclopedia of Islam, p. 324, bold added)

Therefore, we need to realise that the Qur'an has been passed down to us from men

called "the Readers". They were famous reciters of the Qur'an in the early centuries of Islam.

The way these men recited the Qur'an was formerly recorded in textual form by other

men called the "Transmitters".

There are in fact more Readers and Transmitters than those listed above.

The table below lists the commonly accepted Readers and their transmitted versions

and their current area of use.

| The Reader | The

Transmitter | Current Area of Use |

|---|

| "The Seven" |

|---|

| Nafi` |

Warsh Warsh

|

Algeria, Morocco, parts of

Tunisia, West Africa and Sudan |

Qalun Qalun |

Libya, Tunisia and parts

of Qatar |

| Ibn Kathir |

al-Bazzi |

| Qunbul |

| Abu `Amr al-'Ala' |

al-Duri al-Duri

|

Parts of Sudan and West Africa |

| al-Suri |

| Ibn `Amir |

Hisham |

Parts of Yemen |

| Ibn Dhakwan |

| Hamzah |

Khalaf |

| Khallad |

| al-Kisa'i |

al-Duri

|

| Abu'l-Harith

|

| Abu Bakr `Asim |

Hafs Hafs

|

Muslim world in general |

| Ibn `Ayyash |

| "The Three" |

| Abu Ja`far |

Ibn Wardan |

| Ibn Jamaz |

| Ya`qub al-Hashimi |

Ruways

|

| Rawh

|

| Khalaf al-Bazzar |

Ishaq

|

| Idris al-Haddad

|

|

Abu Ammaar Yasir Qadhi, An Introduction to the Sciences

of the Qur'aan, p. 199.

|

What the above means is that the Qur'an has come to us through many

transmitted versions. You cannot recite or read the Qur'an except through

one of these versions. Each version has its own chain of narrators (isnad)

like a hadith. There are more versions than those listed above

but they are not considered authentic because their chain of narration is

considered weak. Not all of these versions are printed or used today,

but several are. We will now compare two of them.

2. A COMPARISON BETWEEN TWO QUR'ANS

All these facts can be a bit confusing when you first read them. If

you are feeling that way don't worry; it's normal. To make things

simple we will now compare two Qur'ans from different parts of the world

to see if they are identical. The Qur'an on the left is now the most

commonly used Qur'an and is according to Imam Hafs' transmitted version.

The Qur'an on the right is according to Imam Warsh's transmitted version and

is mainly used in North Africa.

|

When you compare these Qur'ans it becomes obvious that they are not identical.

There are four main types of differences between them.

- Graphical/Basic Letter Differences

- Diacritical Differences

- Vowel Differences

- Basmalah Difference

|

|

The following examples of these differences are from the same word in the

same verse. On some occasions the verse number differs because the two Qur'ans

number their verses differently. Also, the letter Qaaf in the Warsh version is

written with only one dot, and the Faa has a single dot below.

Graphical/Basic Letter Differences

| THE QUR'AN ACCORDING TO IMAM HAFS |

THE QUR'AN ACCORDING TO IMAM WARSH |

wawassaa wawassaa

Ibrahim enjoin (wawassaa) on his sons ... 2:132 |

wa'awsaa wa'awsaa

Ibrahim left (wa’awsaa) to his sons 2:131 |

| The Warsh version has an extra alif in the word but

in both cases the word means almost the same thing. This seems to be a

difference in dialect.

|

wasaari'uu wasaari'uu

And hasten (wasaari’uu) to ... 3:133 |

saari'uu saari'uu

Hasten (saari’uu) to ... 3:133 |

| The Hafs version has the extra word, "and", in the verse.

This does not change the meaning of the verse but does add an extra word.

|

yartadda yartadda

turn back (yartadda) ... 5:54 |

yartadid yartadid

turn back (yartadid) ... 5:56 |

| The two words are spelt slightly differently but mean the same thing.

This is a difference in dialect.

|

qaala qaala

He said (qaala), "My lord knows ..." (21:4) |

qul qul

Say (qul): My lord knows ... (21:4) |

| These words are spelt differently and mean different things.

This difference changes the subject of the verb.

In the Hafs version the subject is Muhammad,

"He (Muhammad) said, 'My lord knows ...'", but in the Warsh version the subject is

God, "Say: My lord knows ..." as in a command.

|

walaayakhaafu walaayakhaafu

and for him is no fear (walaayakhaafu) ... 91:15 |

falaayakhaafu falaayakhaafu

therefore, for him is no fear (falaayakhaafu) ... 91:15 |

| There are different letters at the beginning of these

words. In this case it does not change the meaning greatly. The Warsh version

has more emphasis.

|

Diacritical Differences

Arabic uses dots to distinguish

certain letters that are written the same way. For instance

the basic symbol  represents five different letters in Arabic depending

upon where the diacritical dots are placed:

represents five different letters in Arabic depending

upon where the diacritical dots are placed:

baa',

baa',

taa',

taa',

thaa',

thaa',

nuun,

nuun,

yaa'.

Here we see another difference

between these two Qur'ans for they do not have the dots in the same place.

The result is that different letters are formed.

yaa'.

Here we see another difference

between these two Qur'ans for they do not have the dots in the same place.

The result is that different letters are formed.

| THE QUR'AN ACCORDING TO IMAM HAFS |

THE QUR'AN ACCORDING TO IMAM WARSH |

nagfir nagfir

we give mercy ... 2:58 |

yugfar yugfar

he gives mercy ... 2:57 |

| There are different letters at the beginning of these words.

This difference changes the meaning from,"we", to, "he". |

taquluna taquluna

you (plural) say ... 2:140 |

yaquluna yaquluna

they say ... 2:139 |

| There are different letters at the beginning of these words.

This difference changes the meaning from,"you", to

"they".

|

nunshizuhaa nunshizuhaa

we shall raise up ... 2:259 |

nunshiruhaa nunshiruhaa

we shall revive/make alive ... 2:258 |

| There are different letters in these words and this makes for two

different words.

The two words have a similar meaning but are not identical.

|

ataytukum ataytukum

I gave you ... 3:81 |

ataynakum ataynakum

We gave you ... 3:80 |

|

There are different letters in these words.

This difference changes the meaning from,"I", to, "we". |

yu'tiihim yu'tiihim

he gives them ... 4:152 |

nuutiihimuu nuutiihimuu

we give them ... 4:151 |

| There are different letters at the beginning of these words.

This difference changes the meaning from "we" to "he". |

Vowel Differences

Arabic uses small symbols above and below the letters

to indicate some of the vowels of a word. Here we see another difference

between these two Qur'ans for they do not have the same vowels in the same place.

| THE QUR'AN ACCORDING TO OF IMAM HAFS |

THE QUR'AN ACCORDING TO OF IMAM WARSH |

yakhda'uuna yakhda'uuna

they deceive ... 2:9 |

yukhaadi'uuna yukhaadi'uuna

they are deceiving ... 2:8 |

| There is a different vowel on the first letter of these words.

This difference affects the tense of the verb. The Warsh version has more of a continuous

meaning.

|

yakdhibuuna yakdhibuuna

they lied ... 2:10 |

yukadhdhibuuna yukadhdhibuuna

they were lied to ... 2:9 |

|

There is a different vowel on the first letter of these words.

This changes the meaning from the active to the passive.

|

yaquula yaquula

he said ... 2:214 |

yaquulu yaquulu

he said ... 2:212 |

| There is a different vowel on the last letter of these words.

This changes the words grammatical connection to the other words in the sentence.

|

ta'aamu miskiinin ta'aamu miskiinin

a redemption by feeding a poor man ... 2:184 |

ta'aami masakiina ta'aami masakiina

a redemption by feeding poor men ... 2:183 |

| There are several different vowels in these words.

This changes the number of men that are required to

be feed in order to redeem yourself for failing to fast.

|

qatala qatala

he killed ... 3.146 |

qutila qutila

he was killed ... 3.146 |

| There are different vowels in these words.

This changes the meaning from the active to the passive.

|

risaalatahu risaalatahu

his message ... 5:67 |

risaalatihi risaalatihi

his message ... 5:69 |

| There are different vowels on the end of these words.

This changes the words grammatical connection to the other words in the sentence.

|

sihraani sihraani

two works of magic ... 28:48 |

saahiraani saahiraani

two magicians ... 28:48 |

| There are different vowels on the first two letters of these words.

This changes the meaning from referring to the magicians to what the magicians did.

|

The Number of Differences

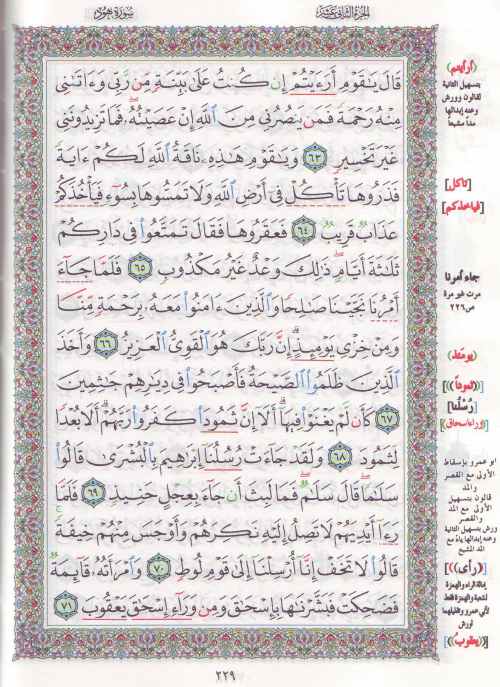

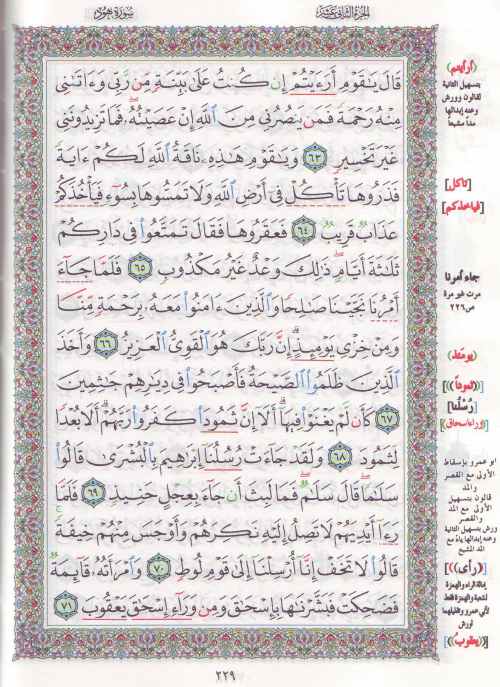

We have now considered three types of differences between these two

Qur'ans: differences in letters, diacritical dots and vowels, but how many of these

differences are there between these two Qur'ans? There are Islamic reference books

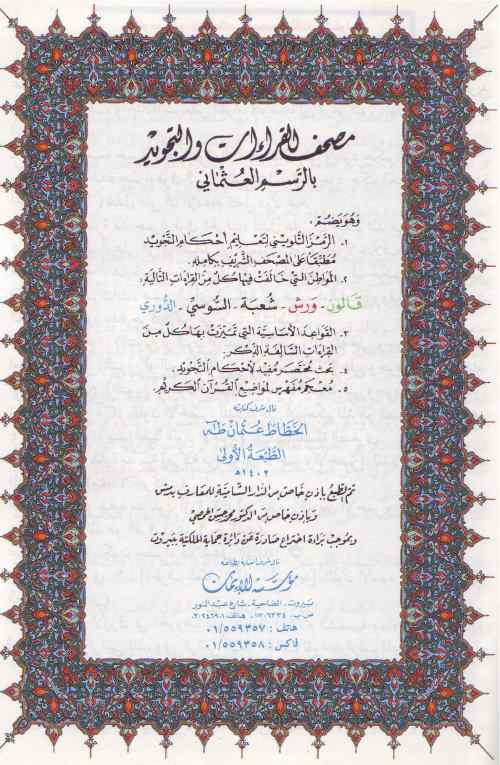

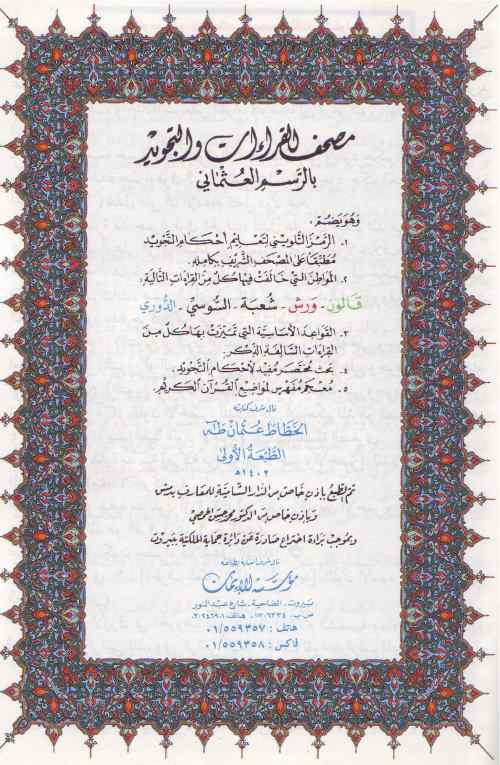

that answer this question. The title page below is from a book entitled,

"The Readings and Rhythm of the Uthman (Qur'anic) Manuscript".

In this book the author uses the Hafs version of the Qur'an but

underlines any word where there is a difference among the Readers.

This difference is then shown in the margin. The author has also used

a colour coded system to show which Reader is different. If the variant word

in the margin is red this indicates that the Reader was Imam Warsh.

Please study the page below and identify the underlined

words and then the corresponding colour coded words

in the margin.

From counting the number of red coded differences in the margin it is

possible to learn how many differences there are between the Hafs and Warsh

versions of the Qur'an. When this is done there are found to be 1354 differences.

Basmalah Differences

There is another type of difference between these two Qur'ans, the Basmalah.

The Basmalah is the phrase, "In the Name of Allaah, the Ever-Merciful, the Bestower of Mercy".

Both the Hafs and Warsh versions of the Qur'an have the Basmalah at the start

of every sura except sura 9. In this way they are identical, however, while including it

in their Qur'ans these Imams understood the Basmalah in very different ways. For

Imam Hafs the Basmalah was part of the first verse as it was recited, while for Imam

Warsh, the Basmalah was a du'a (human supplication) to introduce each sura.

It was written at the start of each sura, like the names, but was not considered part of the revelation.

Abu Ammaar Yasir Qadhi explains this.

The basmalah is the phrase that occurs at the beginning of each soorah

of the Qur'aan, except for Soorah at-Tawbah, and reads, as every Muslim knows,

'Bismillaah ar-Rahmaan ar-Raheem'

(In the Name of Allaah, the Ever-Merciful, the Bestower of Mercy).

There is a difference of opinion amongst the scholars of the Qur'aan over whether

this phrase is to be considered as a verse at the beginning of each soorah, in

particular Soorah al-Faatihah, or whether this is merely a phrase said for

blessings between the soorahs, and is meant to identify where one soorah

ends and the next begins.

The scholars are agreed that the basmalah does not form part of Soorah

at-Tawbah, and that it is a verse of the Qur'an in 27:30 ... but disagree as to its

status at the beginning of the other soorahs ...

The scholars who claim that the basmalah at the beginning of the soorahs

is a verse of the Qur'aan, (include) Imaam ash-Shaafi'ee (d. 204 A.H.) (and) Imaam Ahmad (d. 241)

...

However, those that do not hold the basmalah at the beginning of the soorahs

to be a part of the Qur'aan (include) Imaam Maalik (d. 179) (and) Aboo Haneefah (d. 150 A.H.) ...

Based on this classic difference of opinion, the qira'aat (the Readers) themselves

differ over whether the basmalah was a verse in Soorah al-Faatihah and the other

soorahs. Among the Qaarees (the Readers), Ibn Katheer,'Aasim and al-Kisaa'ee

were the only ones who considered it to be a verse at the beginning of each soorah,

whereas the others did not.

(Abu Ammaar Yasir Qadhi, An Introduction to the Sciences

of the Qur'aan, pp. 157-158.)

To summarize the above. The four Imams who founded the Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i

and Hanbali schools disagree as to whether the Basmalah is part

of the revelation at the start of each sura. Imam ash-Shafi'ee and Imam Ahmad

believed that it was, while Imam Maalik and Aboo Haneefah believed it was not.

As a result the different Readers who come from these schools have different views too.

For Ibn Kathir, al-Kisa'i and Abu Bakr `Asim (Hafs) the Basmalah was part of the

revelation of each sura, but for the majority of the Readers: Nafi` (Warsh),

Abu `Amr al-'Ala', Ibn `Amir, Hamzah, Abu Ja`far, Ya`qub al-Hashimi and

Khalaf al-Bazzar the Basmalah was not part of the revelation.

Therefore, while both of the Qur'ans we are examining contain

the Basmalah, in the Hafs Qur'an it is considered part of the revelation,

while in the Warsh Qur'an it is not considered part of the revelation but du'a.

This is a significant difference between these two Qur'ans.

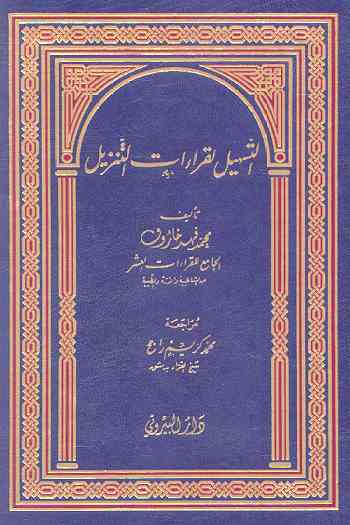

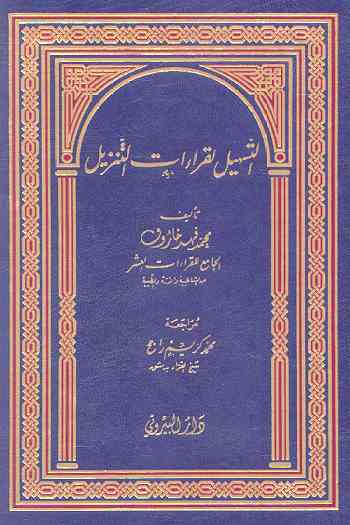

A Qur'an with the Variants of the 10 Readers in the Margin

Our investigation so far has only considered two versions of the Qur'an,

but as we saw at the beginning of this article there are many other versions that

could also be examined for variants. The book below does this. It is a Qur'an

that lists the variants from the Ten Accepted Readers.

Translation

|

Making Easy the Readings of What Has Been Sent Down

Author

Muhammad Fahd Khaaruun

The Collector of the 10 Readings

From al-Shaatebeiah and al-Dorraah and al-Taiabah

Revised by

Muhammad Kareem Ragheh

The Chief Reader of Damascus

Daar al-Beirut

|

This Qur'an is published by a major Middle Eastern publisher. This means that any

Islamic bookshop should be able to order it for you. The copyright page of the book

reads as follows.

|

Copyright is for the publisher.

First Print

1420 - 1999

Can be acquired from Daar al-Beirut Bookshop.

Halabouny, Damascus, Ph: 221 3966

PO Box 25414

|

In this edition of the Qur'an, Muhammad Fahd Khaaruun has collected

variant readings from among the Ten Accepted Readers and included

them in the margin of the Hafs version of the Qur'an.

These are not all the variants.

There are other variants that could have also been

included but the author has limited himself to the variants of

the Ten Accepted Readers. As the title of his

book suggests this makes it easy to know what the variant readings are

because they are clearly listed.

Below is a copy of a random page from this Qur'an. You can see the

variant readings listed in the margin. Approximately two thirds of the verses of the

Qur'an have some type of variant. This is approximately 4000 variants.

3. THE EXTENT TO WHICH THE DIFFERENCES AFFECT THE MEANING

I am often told by Muslims that the differences between these

Qur'ans are only a matter of dialect, accent or pronunciation,

and that they do not have any effect on the meaning at all.

However this is clearly not the case. The examples of the differences

given earlier show that the differences are far more than

dialect, accent or pronunciation. The differences change the subject

of the sentence, whether the verb is active or passive or whether it is

singular or plural. These differences do effect the meaning.

Subhii al-Saalih[3] is an Islamic scholar in this area. He

summarizes the differences into seven categories.

- Differences in grammatical indicator (i`raab).

- Differences in consonants.

- Differences in nouns as to whether they are singular, dual,

plural, masculine or feminine.

- Differences in which there is a substitution of one word

for another.

- Differences due to reversal of word order in expressions where

the reversal is meaningful in the Arabic language in general or in

the structure of the expression in particular.

- Differences due to some small addition or deletion in accordance with

the custom of the Arabs.

- Differences due to dialectical peculiarities.

There is also the difference in the status of the Basmalah.

Therefore, the claim that these differences are just a matter of

dialect, accent or pronunciation and they do not effect the meaning is false.

CONCLUSION. We began this article by considering the

following claim made by a Muslim leader about the Qur'an.

No other book in the world can match the Qur'an ...

The astonishing fact about this book of ALLAH is

that it has remained unchanged, even to a dot,

over the last fourteen hundred years. ... No

variation of text can be found in it. You can

check this for yourself by listening to the

recitation of Muslims from different parts of

the world. (Basic Principles of Islam, p. 4)

This claim is wrong. All of the evidence shows that there are different

versions of the Qur'an used around the world. They have differences in their basic letters,

diacritical dots, vowels and their understanding of the

Basmalah. Therefore how the Qur'an is recited in different parts of the world today is

not identical. Islamic leaders should stop exaggerating about

the Qur'an and tell people about the different versions.

4. APPENDIX 1 - MUSLIM ATTITUDES TO THE DIFFERENT VERSIONS

a. No Islamic scholars accept all of the versions.

In this article we have considered the 10 Accepted Readers and looked

at two of them in particular, however, there are many more Readers/versions

than just these 10.[2] No one accepts all of these versions as authentic,

some are accepted and others are rejected.

They are judged in the same way that the Hadith are judged for their authenticity.

The gradings are: sahih (authentic), shadh (irregular), da'eef

(weak) and baatil (false).[3] In this way the Qur'an is the same as the Hadith.

b. Islamic scholars who say that the all of the authentic versions are

from God.

(T)is oral tradition (of the Qur'an) embraces ten distinct systems of recitation,

or, as they are generally called among scholars, "Readings" (qiraa'aat), each

tranmitted by a "school" of Koran-readers deriving its authority from a prominent

reader of the second or early third century of the Islamic era. The slight variation

among the Ten Readings is attributable to the dialectal variation in the original

Revelation. ... It should be emphasized that all of the Readings were transmitted

orally from the Prophet.

(Labib as-Said, The Recited Koran: A History of the

First Recorded Version, p. 53)

Every reading in accordance with Arabic (grammar) even if (only) in some

way, and in accordance with one of the masaahif of Uthmaan, even if

(only) probable, and with sound chain of transmission, is a correct (Sahiih)

reading, which must not be rejected, and may not be denied, but it belongs to

the seven modes (ahruf) according to which the Qur'aan was revealed, and

the people are obliged to accept it, no matter whether it is from the seven

Imaans, or the ten or from other accepted Imaans (Abu-l-Khair

bin al-Jazari; cited from Ahmad von Denffer, Ulum Al-Qur'an, p. 119.)

c. Islamic scholars who say that the versions are from human error

and that there is only one recitation of the Qur'an.

The Koran was originally recited in one

language and one dialect, namely that of the Quraysh.

However, as soon as readers from the different tribes

began to recite it, a variety of readings emerged, reflecting

dialectal differences among the readers. The diversity

was so great that later generations of readers and scholars

had to labor intensely over the recording and careful analysis

of these readings. In so doing they give rise to a special

science, or rather special sciences, devoted exclusively

to this enterprise. ...

I should pause here to note that certain religious

authorities have supposed that the Seven Readings were

transmitted by a process of continuous transmission

(tawaatur) on a wide scale from the Prophet himself,

unto whom, so they allege, they were revealed by Gabriel.

These authorities therefore consider that whoever rejects

any of the established readings is an unbeliever. They have

not, however, been able to produce any evidence for what

they claim except that the tradition which reads, "The

Koran was revealed in seven dialects (ahruf)".

The truth of the matter is that the seven Readings had

nothing to do with the Revelation, nothing in the least;

and whoever rejects any of them is not for having done so

an unbeliever; nor has he sinned or gone astray in his religion.

The origin of these Readings is to be found in the diversity

of tribal dialects among the early Muslim Arabs, and everyone

has the right to dispute them, and to accept and reject them,

or parts of them, as seems proper.

In point of fact, people have disputed the Readings and

argued over them, and have even accused each other of

error with respect to them; yet we know of no Muslim who

ever charged another with unbelief over this matter (Taahaa Husayn,

Fi'l-Adab al-jaahilii, pp. 98-99; cited from Labib

as-Said, The Recited Koran: A History of the First Recorded

Version, pp. 97-99)

It is generally known that there are seven or ten different recitations

of the Qur'an - By recitation is meant the different wordings which convey

the same or allied meanings Maalik and Malik - Such as

Yatta'harna and Yat'harna. It is generally believed

the recitation of the seven or the ten reciters of the first, second and third

century of Islam are valid and the Muslims are allowed to adopt either of

these in their reciting Qur'an and it is generally held that the origin of

these various recitations go back to the time of the Holy Prophet who approved

these varieties but according to the Shia Ithna-Ashari School whose views are

based on the teachings of the Holy Imams, the revealed recitation of the

Qur'an cannot be but one and as the Imam puts it, "Qur'an is One, came down

from the One, the variation in recitation comes from the reciters not from God."

(S. V. Mir Ahmed Ali, The Holy Qur'an: Text, Translation and Commentary, p. 58a)

5. APPENDIX 2 - WHY ARE THERE SO MANY VERSIONS OF THE QUR'AN?

What situation lead to so many versions of the Qur'an? As we have seen

some Islamic scholars say God gave 7 or 10 different versions of it,

and that these differences were to accommodate the dialectal differences

of the Arabic tribes, and so all of the versions come from God.

However, when the differences are considered few of them are actually dialectal

differences. Most of the differences result from the limitations of the

early Arabic script used to write the Qur'an.

Arabic uses dots to distinguish

certain letters that are written the same way. For instance

the basic symbol  represents five different letters in Arabic depending

upon where the diacritical dots are placed:

represents five different letters in Arabic depending

upon where the diacritical dots are placed:

baa',

baa',

taa',

taa',

thaa',

thaa',

nuun,

nuun,

yaa'.

There are also a series of signs used to indicate vowels.

However these dots and vowel signs were a later development of the

Arabic script and were not used with the early Qur'ans.

Thus the earliest Qur'ans did not have any dots or vowel signs. This meant that

the exact spelling of a word was not written and that what was written could represent

several words if the dots and vowels were placed differently.

Most of the examples of differences that have been considered seem to be the

result of this ambiguity;

they have the same basic letters but have the dots and vowels placed in different

places to make different words.

yaa'.

There are also a series of signs used to indicate vowels.

However these dots and vowel signs were a later development of the

Arabic script and were not used with the early Qur'ans.

Thus the earliest Qur'ans did not have any dots or vowel signs. This meant that

the exact spelling of a word was not written and that what was written could represent

several words if the dots and vowels were placed differently.

Most of the examples of differences that have been considered seem to be the

result of this ambiguity;

they have the same basic letters but have the dots and vowels placed in different

places to make different words.

Here is an Islamic scholar on this subject.

The (Arabic) script used in the seventh century, i.e. during the lifetime of the

Prophet Muhammad, consisted of very basic symbols, which expressed on the

consonantal structure of a word, and even that with much ambiguity. While today

letters such as baa, taa, thaa, yaa, are easily distinguished by points, this was

not so in the early days and all these letters used to be written with a straight

line. ...

When more and more Muslims of non-Arab origin and also many ignorant Arabs studied

the Qur'an, faulty pronunciation and wrong readings began to increase. It is related

that at the time of Du'ali (d. 69H/638) someone in Basra read the following aya

from the Qur'an in a fautly way, which changed the meaning completely:

That God and his apostle dissolve obligations with the pagans (9:3)

That God dissolves obligations with the pagans and the apostle.

This mistake occurred through wrongly reading rasulihi in place of rasuluhu,

which could not be distinguished from the written text, because there were no signs or accents

indicating the correct pronunciation. Unless someone had memorised the correct version

he could out of ignorance easily commit such a mistake. (Von Denffer, `Ulum Al-Qur'an -

An Introduction to the Sciences of the Qur'an, pp. 57-58)

Therefore, while there are some dialectal differences between these versions of the

Qur'an the majority of the differences are the result of the ambiguity of the early

Arabic text. It is this ambiguity of the text that has led to so many different versions.

6. APPENDIX 3 - THE MEMORISATION OF THE QUR'AN

The Qur'an is famous for being memorised. Some Muslims have told me

that it doesn't matter if there are differences between written Qur'ans

because the Qur'an is firstly oral and only secondarily written.

However, the differences

between the written Qur'ans does matter because these written versions

are the records (with the dots and vowels) of the oral recitation of the 10 famous Readers.

That is, the written versions are the memorised oral versions.

Thus the differences between the written versions

are the differences between the memorised oral versions.

Therefore, studying the differences between the written Qur'ans allows us

to make an observation regarding the oral history of the Qur'an.

As was shown, most of the differences between these Qur'ans occurs

at points where the early Arabic script (with no dots or vowels) was

vague and could be read as several Arabic words. As these differences

come from the vagueness of the text, this strongly suggests

that the written text was primary and the memorised oral

versions are secondary and derived from the text.

This provides evidence that these memorised versions cannot all be

traced back to Muhammad but only as far as the establishment of the text.

ENDNOTES

[1] Subhii al-Saalih, Muhaahith fii `Ulum al-Qur'aan,

Beirut: Daar al-`Ilm li al-Malaayiin, 1967, pp. 109ff.

[2] Al-Nadim, The Fihrist of al-Nadim - A Tenth Century survey of Muslim Culture,

New York: Columbia University Press, 1970, pp. 63-71.

[3] Abu Ammaar Yasir Qadhi, An Introduction to the Sciences

of the Qur'aan, United Kingdom: Al-Hidaayah, 1999, pp. 191-192.

REFERENCES

S. V. Mir Ahmed Ali, The Holy Qur'an: Text, Translation and Commentary,

New York: Tahrike Tarsile Qur'an, 1988.

Basic Principles of Islam, (no author listed) Abu Dhabi, UAE: The Zayed

Bin Sultan Al Nahayan Charitable & Humanitarian Foundation, 1996.

Ahmad von Denffer, Ulum Al-Qur'an, UK: The Islamic Foundation, 1994.

Cyril Glassé, The Concise Encyclopedia of Islam, San Francisco:

Harper & Row, 1989.

Al-Nadim, The Fihrist of al-Nadim - A Tenth Century survey of Muslim Culture,

New York: Columbia University Press, 1970.

Subhii al-Saalih, Muhaahith fii `Ulum al-Qur'aan,

Beirut: Daar al-`Ilm li al-Malaayiin, 1967.

Labib as-Said, The Recited Koran: A History of the

First Recorded Version, translated by B. Weis, M. Rauf and M. Berger,

Princeton, New Jersey: The Darwin Press, 1975.

Abu Ammaar Yasir Qadhi, An Introduction to the Sciences

of the Qur'aan, United Kingdom: Al-Hidaayah, 1999.

RELATED READING

Adrian Brockett, `The Value of the Hafs and Warsh transmissions for the Textual History of

the Qur'an', Approaches to the History of the Interpretation of the Qur'an, ed. Andrew

Rippin; Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988, pp. 33-45.

Adrian Brockett,

Studies in Two Transmissions of the Qur'an - PhD Thesis

Grammatical errors in the Hafs

transmission of the Qur'an.

Sunan Abu-Dawud Book 30:

Dialects and Readings of the Qur'an

14 Qira'at Online

The Warsh Version of the Qur'an online.

The author welcomes your response via email.

Copyright © Samuel Green 2005.

This article was updated April 2010.

Further articles by Samuel Green.

The Text of the Qur'an

Answering Islam Home Page

No other book in the world can match the Qur'an ...

The astonishing fact about this book of ALLAH is

that it has remained unchanged, even to a dot,

over the last fourteen hundred years. ... No

variation of text can be found in it. You can

check this for yourself by listening to the

recitation of Muslims from different parts of

the world. (Basic Principles of Islam, p. 4)

No other book in the world can match the Qur'an ...

The astonishing fact about this book of ALLAH is

that it has remained unchanged, even to a dot,

over the last fourteen hundred years. ... No

variation of text can be found in it. You can

check this for yourself by listening to the

recitation of Muslims from different parts of

the world. (Basic Principles of Islam, p. 4)

Warsh

Warsh

Qalun

Qalun  al-Duri

al-Duri

Hafs

Hafs

wawassaa

wawassaa wa'awsaa

wa'awsaa wasaari'uu

wasaari'uu saari'uu

saari'uu yartadda

yartadda yartadid

yartadid qaala

qaala qul

qul walaayakhaafu

walaayakhaafu falaayakhaafu

falaayakhaafu represents five different letters in Arabic depending

upon where the diacritical dots are placed:

represents five different letters in Arabic depending

upon where the diacritical dots are placed:

baa',

baa',

taa',

taa',

thaa',

thaa',

nuun,

nuun,

yaa'.

Here we see another difference

between these two Qur'ans for they do not have the dots in the same place.

The result is that different letters are formed.

yaa'.

Here we see another difference

between these two Qur'ans for they do not have the dots in the same place.

The result is that different letters are formed. nagfir

nagfir yugfar

yugfar taquluna

taquluna yaquluna

yaquluna nunshizuhaa

nunshizuhaa nunshiruhaa

nunshiruhaa ataytukum

ataytukum ataynakum

ataynakum yu'tiihim

yu'tiihim nuutiihimuu

nuutiihimuu yakhda'uuna

yakhda'uuna yukhaadi'uuna

yukhaadi'uuna yakdhibuuna

yakdhibuuna yukadhdhibuuna

yukadhdhibuuna yaquula

yaquula yaquulu

yaquulu ta'aamu miskiinin

ta'aamu miskiinin ta'aami masakiina

ta'aami masakiina qatala

qatala qutila

qutila risaalatahu

risaalatahu risaalatihi

risaalatihi sihraani

sihraani saahiraani

saahiraani