AUTHORSHIP OF BARNABAS.

WAS THE WRITER A JEW OF THE TIME OF CHRIST?

According to the Gospel of Barnabas, the writer, speaking in the first person, claims to be one of Jesus' twelve disciples. He traveled with Jesus throughout Palestine. He was present at the miracles Jesus did. He had heard and knew Jesus' teaching and the teaching of the Jewish leaders. From this we can make the following assumptions.

- He would know who the Jewish High Priest was and when Pilate, the Roman Governor, took office.

- He would know the geography of Palestine having walked around through most of it with Jesus.

- He would know the general plan of the Temple and the feasts of his Jewish religion.

- His native language would be Aramaic, but he would know at least some of the classical Hebrew of the Torah; and if he was educated he would probably know Greek, and possibly even Latin.

- He would know where the hated Roman troops were and approximately how many were stationed in his country.

Having established this picture of a Jew living at the time of Christ, we must now see whether the author of Barnabas shows this knowledge, or not. What we discover is that the Gospel of Barnabas makes errors in every one of these areas.

A. Errors in Knowledge of Who the Leaders Were in His Country

In Chapter 3 of Barnabas we read,

There reigned at that time in Judea, Herod, by decree of Caesar Augustus, and Pilate was governor in the priesthood of Annas and Caiaphas. Wherefore, by decree of Augustus all the world was enrolled; wherefore each one went to his own country ... Joseph accordingly departed from Nazareth, a city of Galilee, with Mary his wife great with child to go to Bethlehem.

The last sentence showing Mary to be "great with child" tells us that the author is speaking about the period when Christ was born. According to the best historical and archeological evidence available Jesus was born in 4 BC. So the Gospel of Barnabas is correct when it says that Herod reigned in Judea when Christ was born.

But what shall we say of the other people mentioned? When we look at secular history we find that Pilate did not become governor until 26 AD and that he held this position from 26 to 36 AD. In other words he was governor when Jesus started preaching, as Luke says correctly in Chapter 3 of his Gospel; but not at time of Jesus' birth in 4 BC, as Barnabas incorrectly says.

As for the priests, Annas was high priest from 6 AD to 15 AD, when he was deposed by the Roman procurator. But he continued to have great authority and was consulted on all important matters and interrogated Jesus when he was captured. Caiaphas, the son-in-law of Annas, was high priest from 18 AD to 36 AD. Again we see that neither of them were in power when Jesus was born in 4 BC. In summary, counting from Jesus' birth in 4 BC, Barnabas is 10 years off with Annas, 22 years off with Caiaphas, and 30 years off with Pilate.

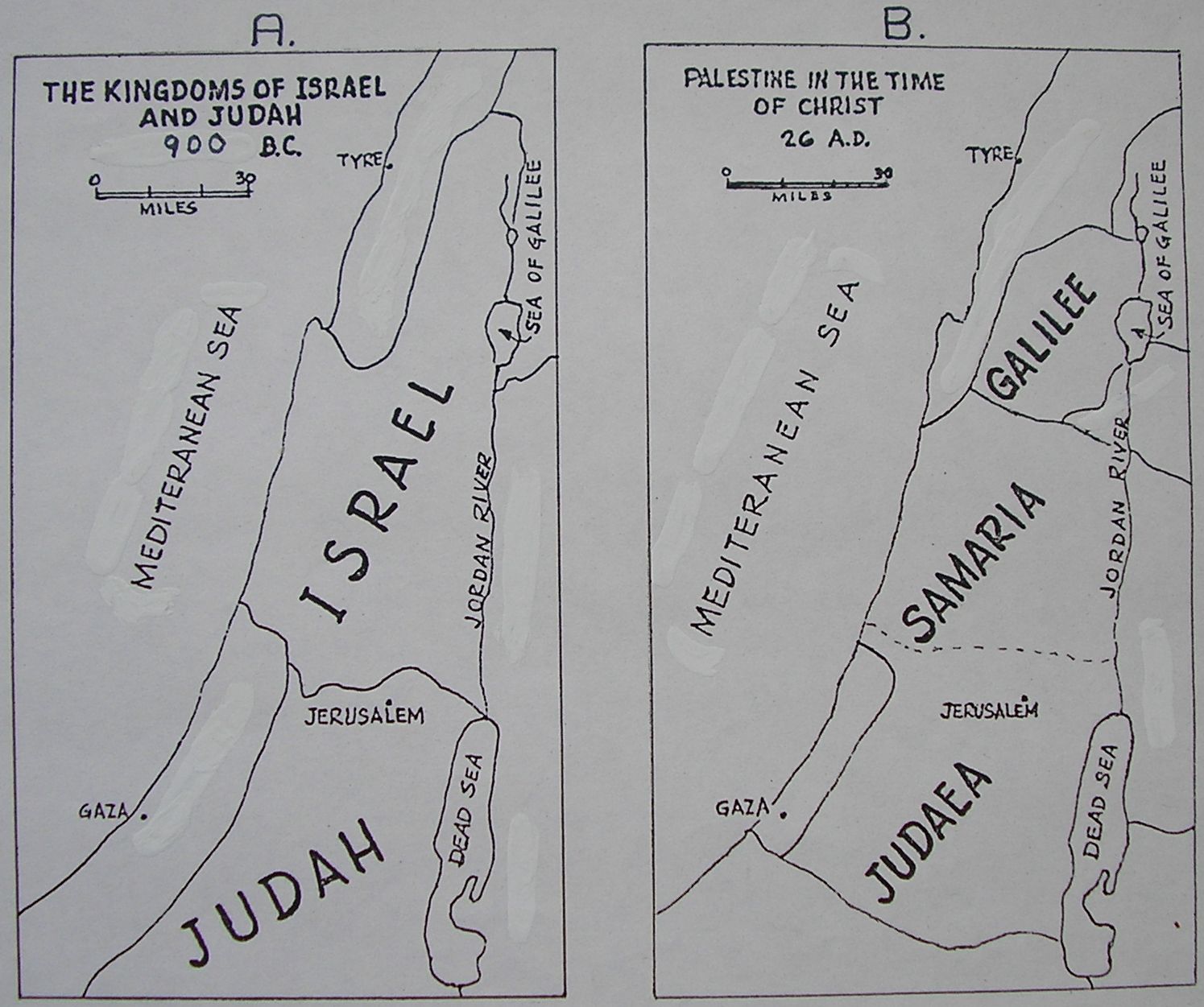

In addition Herod (Antipas) is spoken of as having power and soldiers at his command in Jerusalem and Judea (Chapter 214). This is false for his authority was in Galilee, 60 miles (96 kilometers) away (See figure 2). In Chapter 217 Herod is called a Gentile who "adored the false and lying gods." The truth is he practiced the Jewish law, and believed in one God. The reason he was in Jerusalem to be consulted during Jesus' trial was because he had traveled there from Galilee for the feast of the Passover.

B. Mistakes in Geography

In general, the Gospel of Barnabas repeats the topographical indications contained in the New Testament, but the author makes several mistakes.

i) Position of Tyre (Tiro)

We read in Chapter 99 of the Gospel of Barnabas, that after feeding the 5,000 with five loaves and two fishes,

Jesus, having withdrawn into a hollow part of the desert in Tiro near to Jordan, called together the seventy-two with the twelve.

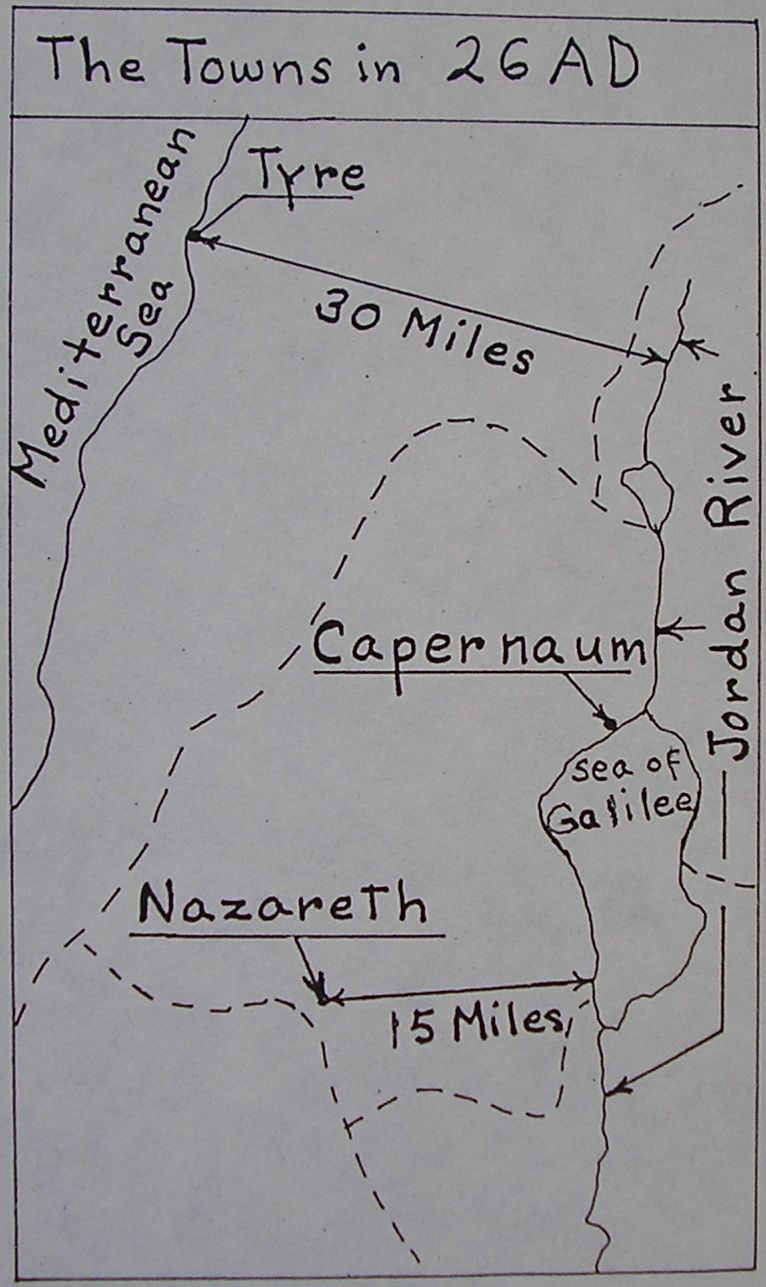

This sentence states that Tiro (Tyre) is near the Jordan River. In fact, Tyre is in present day Lebanon on the shore of the Mediterranean Sea (see Figure 1), more than 30 miles (50 kilometers) from the Jordan River.

ii) Nazareth on the Shore of the Sea of Galilee

In Chapter 20 of the Italian manuscript, we find this curious description. Jesus and his disciples embarked on the sea of Galilee and sailed1 toward Nazareth. On the sea, the miracle of stilling the tempest took place. Then the text continues;

Having arrived at the city of Nazareth, the seamen spread through the city all that Jesus had wrought.

Jesus stayed for a while in Nazareth and then in Chapter 21 it says that he "went up to Capernaum."

Nazareth is thus placed at the shore of the sea and Capernaum is inland. In reality, Capernaum is on the shore of the Sea of Galilee and Nazareth is more than 15 miles away as can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Towns in Palestine in 26 AD

We find the same imprecision later when Jesus decides to go from Damascus to Judea. In one long passage given over to arguments with the Pharisees and descriptions of a true Pharisee, we find at the beginning of Chapter 143 that Jesus left from Damascus and "came to Nazareth." After more discussion, we read in Chapter 151 that "Jesus then embarked on a ship." This passage further confirms our understanding that for the author of Barnabas, Nazareth is on the shore of the sea of Galilee.

iii) He Speaks of Israel and Samaria as Separate Places

During the time of the kings from the tenth to the sixth century BC, Palestine was divided into the northern kingdom of Israel, and the southern kingdom of Judah, as can be seen in map A of Figure 2. In Jesus' day, the northern part of Palestine, formerly called Israel, was made up of two regions called Samaria and Galilee. One no longer spoke of Judah and Israel. One spoke of Judea, Galilee and Samaria. This can be clearly seen on map B in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Palestine in 900 BC and 26 AD

In Chapter 100 of Barnabas the disciples are to go and preach throughout Judea and Israel. But a few lines farther on, the text speaks of passing throughout Samaria, Judea, and Israel. What does the author call Samaria? What does he call Israel? As we have seen on the two maps, "Israel" and "Samaria" are two different names for the same region, but used at different times. The mistake is repeated in Chapter 126 where it says that Jesus sent his disciples throughout "Israel." An eyewitness would have been much more precise.

iv) Nineveh is Placed Near the Mediterranean Sea

It is well-known that the town of Nineveh, the capital of the Assyrian Empire, was built on the eastern bank of the Tigris river, on an outlet known by the name of Al-Khisr in northern Iraq. But in Chapter 63 of Barnabas we read:

Remember that God decided to destroy Nineveh because there was no one in that town who feared Him. He (Jonah) tried to escape to Tarsus (Spain), being afraid of the people, but God threw Him into the sea and a fish swallowed him and cast him out near Nineveh.

For the author of Barnabas, Nineveh is near the Mediterranean Sea, when in reality it was 400 miles away in Iraq.2

In summary, when the author of Barnabas separates himself from the four Canonical Gospels, he almost always falls into error. The Raggs also noted this in 1907. In the preface to their translation they wrote,

His geographical ignorance matches his chronological vaguenes... Evidently he possesses no first hand knowledge of Palestine, still less of Palestine in the first century of our era.3

C. Mistakes in Culture and Religious Knowledge

As we argued in the introduction to this section, we would expect one of Jesus' disciples to know all about the 1st century customs and religious festivals, but in fact, the author of this book makes many mistakes.

i) Culture

a. Wine Casks

In Chapter 152 where we read about the Roman soldiers being miraculously thrown out of the Temple by Jesus, it says,

Whereupon straight-way the soldiers were rolled out of the Temple as one rolls casks of wood when they are washed to refill them with wine.

Now where did these wine barrels come from? Invented in Gaul, they didn't appear in Italy until the lst century. Up to the present no trace of them has been found in archeological excavations of lst century Palestine. If there were any they would have been very rare. The Jews used vessels of pottery to store their wine. It is a word picture from and for the middle ages but it would not be understood in the lst century.

b. 200 Pieces of Gold

In Chapter 6 of John's Gospel where it speaks of the 5,000 men who had spent the whole day with Jesus and were now hungry, the Apostle Philip remarks that "two hundred pennies" would not be enough to buy bread for everyone. Philip is referring to two hundred silver coins each weighing about an eighth of an ounce, a type of Roman money well-known at that time and representing a day's pay. A modern translation makes this clear by using the phrase "eight month's wages",4 and a paraphrase for children has Philip exclaim "It would cost a fortune".5

In the Italian manuscript of Barnabas, Chapter 98, Philip's answer has become, "Lord, two hundred pieces of gold could not buy so much bread that each one should taste a little." But with 200 pieces of gold one could easily buy enough bread for everyone and have a lot left over. Philip's remark then loses all value.

How did this change come about? The English word "pennies" is used to translate the Latin word denarii – singular denarius – which is the word actually used in the Greek New Testament. By the middle ages, the Latin word denarius, slightly transformed to dinar, meant a gold coin. The medieval origin of the Gospel of Barnabas is starting to show through.

ii) Religious Customs

a. "The Forty Days"

What is this fast of 40 days spoken of in Chapter 92 where it says, "And there Jesus with his disciples kept the forty days (allo quadragessima in Italian)"? The writer mentions it as though it would be completely understood by his leaders – as indeed it would be in later Christian periods, because Lent is a late Christian idea. No such fast existed among the Jews of Jesus' day.

b. Regular Prayers Several Times a Day Including Midnight

What are these prayers which Jesus prays regularly – he and everyone with him? Prayers spoken of as being known by all? For example, note the following:

Chapter 155: "Jesus, who was gone out of the Temple, and was sitting in Solomon's porch, waiting to pray the midday prayer.

Chapter 156: "When he had made the midday prayer." (Also Chapter 163)

Chapter 61: "Then Jesus opening his mouth after the evening (prayer)."

Chapter 100: "Every evening when the first star shall appear, when prayer is made to God."

Chapter 83: "After the prayer of midnight the disciples came near unto Jesus."

Chapter 89: "Jesus answered, ‘It is time that we say the prayer of the dawn.’"

Chapter 106: "When he had finished the prayer of the dawn, Jesus sat down."

The author mentions at least four daily prayer times as though they occur at set hours known to everyone. The first century Jews did have a custom of praying three times a day, but there was no prayer at midnight. No Barnabas would have spoken of the "prayer of midnight" at the time of Christ. The author has introduced a custom of the later Christians who prayed, for example, the matin-midnight prayers.

c. The Jubilee

In Chapter 82 we read,

Jesus answered: ‘I am indeed sent to the house of Israel as a prophet of salvation; but after me shall come the Messiah (Muhammad) sent of God to all the world; for whom God has made the world. And then through all the world will God be worshipped, and mercy received, insomuch that the year of jubilee, which now comes every hundred years, shall by the Messiah be reduced to every year in every place.’

What is this jubilee that "now comes every 100 years"? The Jewish year of jubilee was every fifty years (Torah of Moses, Leviticus 25:8-55). The only possible explanation is that "Barnabas" has written his work after the year 1300 AD. Before that date a time span of 100 years would have been considered a complete error. After that date, everything becomes clear. Barnabas makes an allusion, not to the Jewish Jubilee, but to a Christian Jubilee instituted by Pope Boniface VIII. It was to be celebrated every 100 years and was celebrated for the first time in 1300 AD. Part of this Christian Jubilee was that the believers should receive forgiveness of sin. Later Popes changed it, first to 50 years, then to 33 year intervals, and finally every 25 years. Since 1450 the Holy Years have been celebrated at this interval.6

The author of Barnabas seems to know about this reduction too. For as we saw above he writes, "the year of jubilee ... shall by the Messiah be reduced to every year." This passage, by itself, is very strong evidence that the work was written after 1300 and indeed long enough after 1300 so that the reduction in intervals had already begun. In any case, there was no such thing as a Jewish year of Jubilee every 100 years when Jesus was walking around in Palestine.

D. Language Errors

i) The Pinnacle of the Temple

The author does not know what is meant by the pinnacle of the Temple (pinocholo in Italian). According to his use of the word he seems to understand it to be the place where the scribes stood to preach. In Chapter 12 it says,

Therefore the priests besought Jesus, saying: ‘This people desires to hear you and see you; therefore ascend to the pinnacle and if God gives you a word speak it in the name of the Lord.’ Then Jesus ascended to the place whence the scribes were wont to speak.

Again in Chapter 127-129 we read,

So after the reading of the Psalms Jesus mounted up on the pinnacle where the scribe used to mount, and, having beckoned for silence with his hand, he said, ‘Blessed he the Holy name of God...’ And having said this, Jesus prayed... When he had finished his prayer he descended from the pinnacle.

The person who made the Arabic translation understood the word in the same way and translated the Italian pinocholo with the Arabic word dikka (دِكَّة) the platform from which one speaks in the mosque. But, in reality, the pinnacle was a high point on the exterior border at the top of the temple from where one could easily feel dizzy and risk falling. It was certainly not the place from which the scribes spoke to the people.

ii) Meaning of the Word Pharisee

The author speaks of Pharisees often and at great length, and in Chapter 144 he talks of their origin and the meaning of the word. We read,

(Jesus said) Tell me, know ye your origin, and wherefore the world began to receive Pharisees? Surely I will tell you... Enoch, a friend of God, who walked with God in truth... was translated into paradise... And so men, having knowledge of this, through desire of paradise, began to seek God their creator. For "Pharisee" strictly means "seeks God" in the language of Canaan, for there did this name begin by way of deriding good men, seeing that the Canaanites were given up to idolatry which is the worship of human hands. Whereupon the Canaanites beholding... such a one, said ‘Pharisee!’ that is, ‘He seeks God.’

And in Chapter 145 we read,

As God lives, in the time of Elijah, friend and prophet of God, there were twelve mountains inhabited by seventeen thousand Pharisees; and so it was that in so great a number there was not found a single reprobate, but all were elect of God.

From this it is clear that the author believes that the word "Pharisee" means "seeks God", and that the Jewish religious group known as the Pharisees started when the Canaanites had power in Palestine. This would place it before the time of David who eliminated all foreign rule in that country – that is, before 1000 BC. According to the Gospel of Barnabas the group grew so that when Elijah was a prophet in the 9th century BC there were 17,000 of them.

As we read on in Chapters 145-150 we find that the Pharisees are described as a religious movement, organized into a "congregation", following "the rule" formed by Elijah, and wearing a special uniform or robe – "the habit of the Pharisees."

They are told to live in solitude, speaking with men once a month; to rise from the table hungry; to sleep two hours a night and that only on the earth; all this as though they were a congregation of monks from the middle ages.

In fact, the movement of the Pharisees only dates from the second century before Jesus. They are not mentioned in any of the literature concerning the Maccabean revolts from 168 to 135 BC, revolts in which a patriotic and zealous movement such as the Pharisees would surely have participated. The earliest historical reference to them which can be dated is in Antiquities of the Jews xiii. 10. 5f by Josephus where he reports a schism between the Pharisees and John Hyrcanus, a Jewish ruler who was at the same time High Priest and who died in 104 BC.

The Pharisees were not monks, but people living in the world and usually married. Certain of them even recommended learning a manual trade in a spirit of simplicity and humility. In addition the word "pharisee" is a Hebrew word which does not mean "seeks God". It probably means "separated". The Pharisees were the separated ones. A Jewish contemporary of Jesus would never describe the Pharisees in the terms used by the author of Barnabas.

iii) Feast of Tabernacles

In Chapter 15 of Barnabas we read, "When the feast of Tabernacles was near, a certain rich man invited Jesus..." This phrase written in Italian as "la festa di Tabernacholi" is correct. The Jews had such a feast (Torah of Moses, Leviticus 23:33-36) and Jesus surely celebrated it. However, in Chapter 30 of Barnabas, which is still describing the first year of Jesus' ministry (see Chapter 47), we read,

Jesus went to Jerusalem, near into the Senofegia, a feast of our nation.

The problem is that this word "Senofegia" is a deformation of the Greek word skenopegia which means tabernacles. The author has made Jesus celebrate the "feast of tabernacles" twice in one year because the author does not know that the Greek word senofegia means exactly the same as the Latin tabernacholi.

iv) The Pool Called Probatica

In Chapter 65 of Barnabas we find,

And he (Jesus) went to the pool called Probatica. And the bath was so called because the angel of God every day troubled the water, and whosoever first entered the water after its movement was cured of every kind of infirmity.

For the author of Barnabas the meaning of the word "probatica" is located in the phrase which follows – viz., either in the "troubling or movement of the waters", or perhaps the "healing". In fact, the word has no such meaning. It means simply "of the sheep" in Greek and is so utilized in the Gospel according to John 5:2 where we read, "Now there is in Jerusalem near the gate of the sheep (probatica) a pool which in Aramaic is called Bethesda." Again the author errs because he does not know the meaning of the Greek word "probatica". The Raggs in the introduction to their 1907 translation, give several examples showing that the author of Barnabas was actually using the Vulgate, a Latin translation of the 4th century, as the basis for his Biblical knowledge and had little or no understanding of Greek, the language in which most of the New Testament was originally written.

E. Errors Concerning the Roman Military Power in Palestine During the Time of Jesus' Ministry

To have a quick overall view of how Rome distributed its troops at the time of Christ, we need only to look at the Annals of the Roman historian Tacitus who lived from about 55 to 117 AD. In Book IV, Chapters 4 and 5, he writes about the distribution of Roman troops under the reign of the Emperor Tiberius who ruled from 14 to 37 AD. We read as follows,

Tiberius also rapidly enumerated the legions and the provinces which they had to garrison. I too ought, I think, to go through these details, and thus show what forces Rome then had under arms, what kings were our allies, and how much narrower then were the limits of our empire.

Italy on both seas was guarded by fleets, at Misenum and at Ravenna... But our chief strength was on the Rhine, as a defense alike against Germans and Gauls, and numbered eight legions. Spain, lately subjugated, was held by three. Mauritania was king Juba's who had received it as a gift from the Roman people. The rest of Africa was garrisoned by two legions, and Egypt by the same number. Next, beginning with Syria, all within the entire tract of country (which included Palestine) stretching as far as the Euphrates, was kept in restraint by four legions, and on this frontier were Iberian, Albanian, and other kings, to whom our greatness was a protection against any foreign power. Thrace was held by Rhomatalces and the children of Cotys; the bank of the Danube by two legions in Pannonia, two in Mossia, and two also were stationed in Dalmatia, which, from the situation of the country, were in the rear of the other four, and, should Italy suddenly require aid, not too distant to be summoned. But the capital was garrisoned by its own special soldiery, three city and nine praetorian cohorts, levied for the most part in Etruria and Umbria, or ancient Latium and the old Roman colonies.

When we add up these numbers we see that there were just 25 legions, or 150,000 Roman soldiers from Spain to the Euphrates river. In addition there were probably another 200,000 auxiliaries for a grand total of 350,000 men to keep the peace in the whole Roman Empire.

i) Roman Forces in Tunisia as an Example

As an example of the way in which Rome stationed its troops during the time of Tiberius, we shall consider Tunisia. The Roman military strategy is clearly outlined in Histoire de la Tunisie – L'Antiquité in the section "Rome et L'Apogée" by Ammar Mahjoubi.7 He states,

For the defense of the occupied territory, Rome maintained only a feeble army of occupation: one legion of 5,500 men and a slightly larger number of auxiliaries – foot soldiers, and especially cavalry; for a total of 13,000 men.

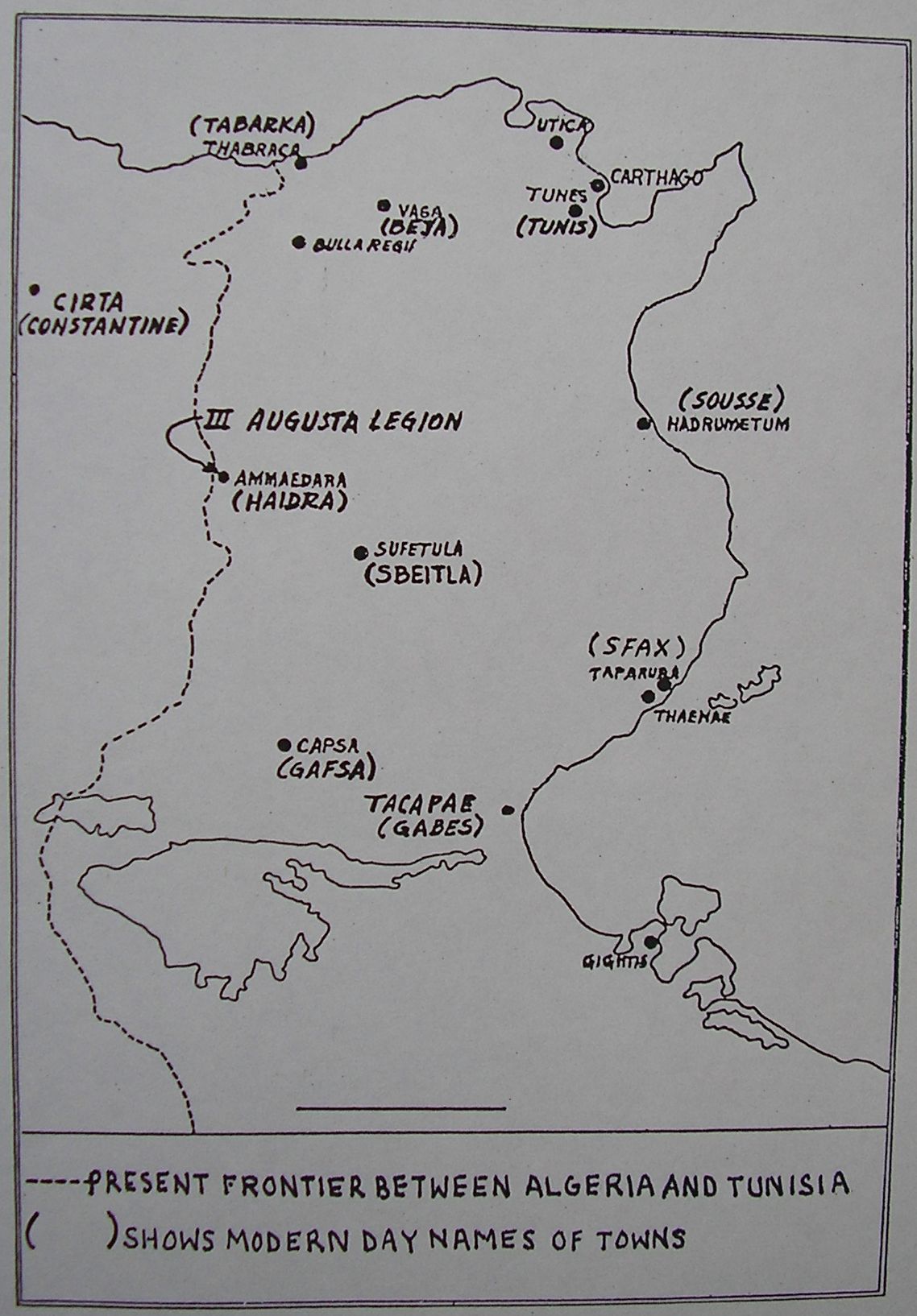

Figure 3 Roman Tunisia

He goes on to say that at the time which interests us the legion was limited to Roman citizens (though this changed later), and the auxiliaries were recruited from provinces outside Africa. Many inscriptions have been found giving their names as coming from Spain, Chalcedon in Turkey, etc. During the reign of Tiberius the III Augusta legion was stationed at Ammaedara represented in present day Tunisia by a small village called Haïdra a few miles west of Thala on the Tunisian border with Algeria. At the same time they built a road from Tacapae (present day Gabès) to Ammaedara (Haïdra) to complete their system of roads which permitted quick displacement of troops to trouble points. Although southern Tunisia was not included in their area, a large section of Algeria over as far as Constantine was under their surveillance, as can be seen on the map in Figure 3. Finally, according to the same source,8 order was assured in Carthage the capital by one cohort of 600 men detached from the 3rd legion, and who acted under the authority of the proconsuls.

In summary then, 13,000 soldiers were sufficient to keep the peace in an area of more than 50,000 square miles.

ii) The Situation in Palestine

In Palestine with an area of about 10,000 square miles the situation was similar except that Rome was doubly hated by the Jews. They were hated, of course, for occupying the country, but they were hated even more for their idolatry. The result was that groups of Jews often rose in revolt.

Because of this possibility of revolt, the Romans could not trust the Jews to be auxiliary soldiers and they were exempted from military service. Pilate was the local governor and representative of Caesar with Roman soldiers at his command. But because Palestine was smaller, he had fewer soldiers to keep the peace. There was a small unit of cavalry and several cohorts – each one of 600 men, for a total of not more than 3,000 men in the whole country.9

The Romans were suspicious of large gatherings. They knew that the people tolerated their domination very badly. A Roman garrison, in the fortress of Antonia, watched over the Temple at all times. And at the great feasts, the procurator left his capital at Caesarea and went up to Jerusalem to be ready to act if necessary. It was because of the feast of the Passover that Pilate was in Jerusalem and could try Jesus in 30 AD.

iii) Soldiers in Palestine According to the Gospel of Barnabas

a. In Chapter 91 we read,

Thereupon, to quiet the people, it was necessary that the high priest should ride in procession, clothed in his priestly robes, with the holy name of God, the teta gramaton,10 on his forehead. And in like manner rode the governor Pilate, and Herod. Whereupon, in Mizpeh assembled three armies, each one of two hundred thousand men that bore sword.

What are we to say when we read that the Jewish high priest had 200,000 soldiers and the Jewish vassal king Herod had 200,000 soldiers? If these men were Jews – 400,000 Jews – they would have risen in revolt against the 200,000 Romans in order to have their independence. If we are to understand that they were all Roman soldiers and auxiliaries, it would represent more Roman soldiers than actually existed at that time in the whole Roman Empire, and 200 times the number present in Palestine.

We saw above that Tacitus said,

Next (after Egypt) beginning with Syria, all within the entire tract of country stretching as far as the Euphrates (including Palestine), was kept in restraint by four legions.

In other words 24,000 soldiers, plus auxiliaries, had the task of keeping the peace in about 100,000 square miles of territory, an area 10 times that of Palestine. To speak of 600,000 soldiers in Palestine alone is a comedy.

b. The same type of error is found in Chapter 210 where we read,

Then the governor (Pilate) feared the senate and made friends with Herod... and they joined together for the death of Jesus, and said to the high priest: ‘Whenever thou shalt know where the malefactor is, send to us, for we will give thee soldiers.’

Now why does the high priest need soldiers if he already has 200,000?

c. Again in Chapter 214 with Judas speaking:

‘If you will give me what was promised, this night will I give into your hand Jesus whom you seek; for he is alone with eleven companions.’ The high priest answered: ‘How much seekest thou?’ Said Judas, ‘Thirty pieces of gold.’ Then straightway the high priest counted unto him the money, and sent a Pharisee to the governor to fetch soldiers, and to Herod, and they gave a legion11 of them (6,000 soldiers), because they feared the people.

First of all it is unthinkable to send 6,000 soldiers to arrest 12 men. Secondly, the high priest already had 200,000 men. Thirdly, as we saw above, Herod had no power or authority to have or provide soldiers in Jerusalem, as he was the tetrarch of Galilee. Fourthly, as we saw in the historical overview, there was not a legion in all of Palestine and probably not more than a cohort in Jerusalem, which at that time had a normal population of about 60,000 people.12 Barnabas as an eye-witness should have known all these things.

d. The final error concerning Roman soldiers is found in Chapter 152. Some of them are in the Temple talking with Jesus and he says to them,

‘Assuredly, seeing (the Roman idols) make not a single fly afresh, I will not for them forsake that God who hath created everything with a single word; whose name alone affrighteth armies.’ The soldiers answered: ‘Now let us see this; for we are going to take thee,’ and they were going to stretch forth their hands against Jesus. Then said Jesus, ‘Adonai Sabaoth!’ Whereupon straightway the soldiers were rolled out of the Temple as one rolleth casks of wood when they are washed to refill them with wine; insomuch that now their head and now their feet struck the ground, and that without any one touching them. And they were so affrighted and fled in such wise that they were never more seen in Judea.

That the soldiers were afraid after being thrown out of the Temple miraculously, and that they fled back to the fortress of Antonia, mentioned above, could obviously be true. But that they "fled in such wise that they were never more seen in Judea" seems very unlikely. The punishment for desertion was death. One can only conclude that being rolled out of the Temple, while turning end over end like pins on a bowling alley, and leaving the country completely is not being serious. It is farce and comedy.

iv) First Century History as Recorded by Luke

In contrast when we look at the story of Paul's imprisonment in Jerusalem recorded in the Book of Acts Chapters 21 and 23 of the Holy Bible, we find that it agrees with secular history in every particular. In Acts 21:26-33 we find the following incident related. Some of the most orthodox Jews had seen Paul walking around Jerusalem with a Greek Christian. They thought that Paul had brought the foreigner into the Temple and desecrated it so they stirred up the crowd.

Then all the city was aroused, and the people ran together; they seized Paul and dragged him out of the temple, and at once the gates were shut. And as they were trying to kill him, word came to the tribune of the cohort13 that all Jerusalem was in confusion. He at once took soldiers and centurions, and ran down to them; and when they saw the tribune and the soldiers, they stopped beating Paul. Then the tribune came up and arrested him, and ordered him to be bound with two chains.

Next a plot was made by the Jews to kill Paul and the account continues as follows (Acts 23:16-24):

Now the son of Paul's sister heard of their ambush; so he went and entered the fortress and told Paul. And Paul called one of the centurions and said, ‘Take this young man to the tribune; for he has something to tell him ...’

(The boy spoke to the tribune and said) ‘The Jews have agreed to ask you to bring Paul down to the council tomorrow, as though they were going to inquire somewhat more closely about him. But do not yield to them; for more than forty of their men lie in ambush for him, having bound themselves by an oath neither to eat nor drink till they have killed him; and now they are ready, waiting for the promise from you.’ So the tribune dismissed the young man, charging him, ‘Tell no one that you have informed me of this.’ Then he called two of the centurions and said, ‘At the 9th hour of the night get ready two hundred soldiers with seventy horsemen and two hundred spearmen to go as far as Caesarea. Also provide mounts for Paul to ride, and bring him safely to Felix the governor.’

So the (foot) soldiers, according to their instructions, took Paul and brought him by night to Antipatris. And on the morrow they returned to the fortress, leaving the horsemen to go on with him. When they came to Caesarea and delivered the letter to the governor, they presented Paul also before him.

We see that Paul was thrown out of the Temple because the Jews thought that he had brought an uncircumcised pagan Greek in and desecrated it. They closed the door of the Temple and started to kill him. The sound came to the tribune of the cohort (Acts 21:31,32) who took soldiers and centurions to put down the disturbance. In Chapter 23:16 Paul's nephew came to the fortress to warn Paul. After hearing the news the tribune called two centurions to prepare 200 foot soldiers, 70 horsemen, and two hundred spearmen. Leaving at 9 P.M. they went in full strength at walking speed down one of those famous Roman roads until they had gone 30 miles to Antipatris. Then the foot soldiers went back to the fortress and the cavalry quickly finished the remaining 30 miles to Caesarea.

Luke was a first century Christian author. His description of Paul's arrest in Jerusalem is in complete agreement with what we know about Jerusalem under Roman occupation.

What a contrast to the false information given by the author of Barnabas. It's plain that he was never there.

Summary

We have now discussed 25 historical, geographical and cultural errors in great detail. We could go on and discuss the statement in Chapter 217 that "the council of the Pharisees" judged Jesus. When in fact the Sanhedrin or Jewish high court was controlled by powerful members of another Jewish religious group called the Sadducees. We could discuss the use of the word Ishmaelites in Chapter 142 – a word no longer in use at the time of Christ. But it would change nothing. The general theme of Jesus who affirms that he is not the Messiah, the numerous erroneous details – historical, geographical, cultural, religious, and linguistic all lead to the same conclusion.

It is impossible that the Gospel According to Barnabas was composed by a "Barnabas" who lived in Palestine at the beginning of the first century, and to this even some Muslim scholars agree.

Testimony of Muslim Writers that the Gospel of Barnabas is a Forgery

In his book The Gospel of Barnabas, in the Light of History, Reason and Religion, the author Aaod Simaan writes.14

Some Muslims scholars have studied the Gospel of Barnabas extensively and agree completely with what we have found.

He notes particularly the following two authors.

A. Professor Aabas Mahmoud Aqad writing about Barnabas in the newspaper Al Akhbar, published October 26, 1959 makes five principal points.

First he notices that many expressions used in the Gospel of Barnabas were not known before the spread of Arabic into Andalusia. Secondly, the description of hell "leans" on late facts not known among Hebrew Christians at the time of Christ (see Chapter IV). Thirdly, some expressions found in it had penetrated into the continent of Europe from Arab sources. Fourthly, the Messiah did not customarily tell the crowds his message in the name of "Muhammad, the Apostle of God." And fifthly, some mistakes mentioned in this gospel are of the type that the Jew familiar with the books of his people would not be ignorant of, and the Christian of the Western Church who believes in the Canonical Gospels does not repeat, and the Muslim who understands the contradictions in the Gospel of Barnabas between it and the Qur'an, will not become involved in them.

B. Dr. Muhammad Chafiq Ghorbal writing in the Arabic Encyclopedia, Al Misra under the heading "Barnabas", said as follows:

A forged (or Pseudo) Gospel produced by a European in the 15th century; and in its description of the political and religious condition in Palestine at the time of the Messiah, full of errors. For example, it places on the tongue of 'Isa (Jesus) that he is not the Messiah, but that he came to announce Muhammad who will be the Messiah.

Conclusion

In the light of all this information, we can only conclude that the Gospel of Barnabas has no historical value as an original first century document. From now on we shall refer to it as Pseudo-Barnabas, and in the next chapter we shall consider evidence which shows that it was composed much later – many centuries after the time of Christ.