The Haman Hoax

Appendix 4

A documentation of various versions of the argument made by Islamic Awareness regarding the name "Haman" and its alleged occurrence in Egyptian inscriptions

After the publication of this investigative article (*), Islamic Awareness will not have any other option than to abandon their woefully wrong argument that has misled so many people. This means their (current) argument will (soon? eventually?) disappear from their website (although it is quoted / replicated by Muslims in many other places1) and be replaced by something substantially different. This appendix has the purpose to preserve their orginal argument(s) so that future readers can still compare their (original) arguments with our responses on Answering Islam [1, 2 (by Andrew Vargo), 3 (the present rebuttal by Jochen Katz)].

When this series was first published, this appendix contained only two versions, called Version 1 and Version 2. However, I later re-discovered various earlier versions which were of some interest for this discussion. Though it made things a bit more complicated, this appendix was therefore expanded and I was forced to renumber the versions. What was "Version 1" originally is now Version 1.6, and what was "Version 2" is now Version 2.2. Thus, when other parts of this series mention the first version or first edition then this refers to what is now listed as Version 1.6. This appendix preserves versions 1.0, 1.5, 1.6 and version 2.2 for the following reasons:

In the main article I trace the development of their argument, notably the disappearance of footnote 41 from version 1.6 to version 2.0 which is relevant for my response to Bucaille. Since versions 2.0 (27 January 2006), 2.1 (12 March 2006) and 2.2 (4 June 2006) differ only minimally, I chose to only display the latest of these versions which is also the current version (as of 9 November 2009).

Version 1.0 is interesting mainly for the reason that it displays the authors’ confident and unquestioning faith in the claims of Maurice Bucaille and their definite identification of the Haman of the Qur'an with the "Haman" mentioned on the (alleged) stela. At that time, they had not yet taken the effort to even identify the books by Ranke and Wreszinski mentioned by Bucaille. Because of the subsequent newsgroup discussion between M S M Saifullah and myself,2 they were forced to search for those books, identify them and provide proper bibliographical references as well as making attempts to bestow meaning on some of Bucaille’s mysterious statements. This resulted in several updates of their article. I will only display versions 1.5 and 1.6.3

Versions 1.5 and 1.6 are both interesting to preserve because up to version 1.5 Islamic Awareness did little more than parotting Maurice Bucaille4 and their false claims could perhaps still be "excused" due to ignorance. Version 1.6, however, was a revision that was published after they knew considerably more. They changed very little and propagated essentially the same claims even though they knew them to be wrong. The evidence for this conclusion is presented in Appendix 6. Thus, between 1.5 and 1.6 ignorance changed to deliberate deception. In other words, they moved from being deceived by the hoax created by Bucaille to becoming active co-conspirators in it, deceivers for the sake of defending and promoting Islam.

Harun Yahya's first (and second) version is largely based on version 1.4 of the article by Islamic Awareness. (See here.)5

Version 2.0 meant a huge change over version 1.6 since the authors moved from claims to arguments, i.e. they realized that Bucaille had only issued unsubstantiated claims which were in need to be supported with actual arguments. Sadly, they chose to support false claims by deceptive arguments based on misrepresenting their sources as shown in my examination of their article.

In this appendix I will only quote those parts of their article(s) that are relevant to our present discussion, i.e. the question of whether or not the name of Haman was found in ancient Egyptian records. The bulk of their paper consists of an attack on the authenticity of the biblical Book of Esther (sections 2-3) and various other aspects from the story of Moses and Pharaoh in the Qur'an (section 4.1-4.4)6 which have no direct bearing on this particular question. The parts that are omitted are indicated with three dots in curly brackets {...}.

The below reproduced versions 1.5, 1.6 and 2.2 were all published under the same title and web address: Historical Errors of the Qur'an: Pharaoh & Haman

Version 1.0 was posted by M S M Saifullah to the newsgroup soc.religion.islam (SRI) on 11 May 1998.7

Version 1.0 |

{ 11 May 1998 }

Pharaoh, Haman, Contradictions & The Qur'an

This document is to establish the historical nature of some of the

statements made in the story of Moses(P) in Egypt in the Qur'an. To begin

with:

{...}

Who Is This Haman?

------------------

Dr. Maurice Bucaille narrates an interesting discussion he had with one of

the most prominent French Egyptologists:

I showed him the word Haman that I had copied exactly like it

is written in the Qur'an, and told him that it had been

extracted from a sentence of a document dating back to the 7th

century, the sentence related to somebody connected with

Egyptian history.

He said to me that, in such a case, he would see in this word

the transliteration of a hieroglyphic name but, for him,

undoubtedly it could not be possible that a written document

of the 7th century had contained a hieroglyphic name - unknown

until that time - since, in that time, the hieroglyphs had

been totally forgotten.

In order to confirm his deduction about the name, he advised

me to consult the Dictionary of Personal Names of the New

Kingdom by Ranke... I was stupefied to read the profession of

Haman: "The Chief of the workers in stone-quarries,"

exactly what could be deduced from the Qur'an, though the

words of the Pharaoh suggest a master of construction.

I came again to the expert with a photocopy of the page of the

Dictionary concerning Haman and showed him one of the pages of

the Qur'an... he was speechless...

Moreover, Ranke had noted, as a reference, a book published in

1906 by the Egyptologist Walter Wreszinski: the latter had

mentioned that the name of Haman had been engraved on a stela

kept at the Hof-Museum of Vienna (Austria). [[13], pp. 192-193]

And he went on to say:

Several years later, when I was able to read the profession of

written in hieroglyphs on the stela, I observed that the

determinative joined to the name had emphasized the importance

of the intimate of Pharaoh. [[13], pp. 193]

It is clear from the stela that Haman was the intimate of Pharaoh as the

Qur'an describes it. So, Haman is a historical figure from ancient Egypt.

However, non-Muslim scholars have claimed that Haman is unknown to

Egyptian history.

We will reverse the question and apply it to the Bible:

"Haman occurs in the (Qur'anic story) in Egypt, 1,100 before the story of

Esther. Haman is not a Babylonian name but Egyptian."

The reference to Haman in the story of Esther in the Bible is an anachronism.

Conclusions

-----------

In this article we have tried to show the historicity of various

statements concerning Egypt in the Qur'an. This includes the role of the

Pharaoh in Egyptian society as god, his manner of addressing other gods,

the person Haman and the use of bricks in Egyptian construction.

It is also worth noting that the issue of Haman provides a death-blow to

the Bible-borrowing theory of the Qur'an. If hieroglyphs were long dead

and the Book of Esther had a doubtible history then from where Prophet

Muhammad(P) was getting his information? The Qur'an answers:

Your Companion is neither astray nor being misled. Nor does he say

(aught) of (his own) Desire. It is no less than inspiration sent down to

him. He was taught by one mighty in Power. [Qur'an 53:2 - 5]

It is interesting to know that the meaning of ayah i.e., verse of the

Qur'an is a sign and a proof. The existence of Haman and other facts

concerning ancient Egypt in the Qur'an suggests a special reflection.

There is more information that needs to be researched concerning

Egyptology in the Qur'an. We will be updating the information on this page

as soon as new references are obtained, inshallah.

And Allah knows best.

References

----------

{...}

[13] Moses and Pharaoh: The Hebrews in Egypt: 1995, Dr. M. Bucaille, NTT

Mediascope Inc., Tokyo.

Version 1.5 |

Historical Errors Of The Qur'ân: Pharaoh & Haman

Elias Karîm, Qasim Iqbal & M S M Saifullah

© Islamic Awareness, All Rights Reserved.

Last Updated: 11 May 1999

Assalamu-alaikum wa rahamatullahi wa barakatuhu:

1. Introduction

Controversy has prevailed since 1698 CE about the historicity (i.e., historical reality or authenticity) of a certain Haman, who according to the Qur'ân, was associated with the Court of Pharaoh to whom Moses(P) was sent as a Prophet by Almighty God (Allah):

Pharaoh said: "O Haman! Build me a lofty palace, that I may attain the ways and means- The ways and means of (reaching) the heavens, and that I may mount up to the god of Moses: But as far as I am concerned, I think (Moses) is a liar!" [Qur'ân 40:36-37]

Haman is mentioned six times in the Qur'ân and is referred to as an intimate person belonging to the close circle of Pharaoh.

Western scholars have concluded that Haman is unknown to Egyptian history. The name Haman is first mentioned in the Biblical book of Esther, some 1,100 years after Pharaoh. The name is said to be Babylonian, not Egyptian. According to the book of Esther, Haman was a counsellor of Ahasuerus (the Biblical name of Xerxes) who as an enemy of the Jews. It has been suggested that Muhammad(P) mistakenly mixed Biblical stories and Jewish myths of the Tower of Babel, the story of Esther and Moses into a single confused account when composing the Qur'ân.

We propose here to examine the various aspects of the controversy in light of recent historical and archaeological discoveries.

{...}

4. Pharaoh & Haman In The Qur'ân

Let us now examine the passages in the Qur'ân concerning the Pharaoh and Haman in light of recent historical and archaeological discoveries.

{...}

4.3 The Making Of Bricks In Ancient Egypt

Pharaoh said: "O Haman! light me a (kiln to bake bricks) out of clay, and build me a lofty palace, that I may mount up to the god of Moses: but as far as I am concerned, I think (Moses) is a liar!" [Qur'ân 28:38]

Were mud bricks made and burnt in the ancient Egypt? It is a well known fact, borne out by archaeological research, that mud bricks and baked bricks were manufactured in ancient Egypt:

{...}

4.5 The Mystery Of The Name Haman

Haman is mentioned six times in the Qur'ân: surah 28, verses 6, 8 and 38; surah 29, verse 39; and surah 40, verses 24 and 36. He was close to Pharaoh who, boastful and mocking, said:

"O Haman! Build me a lofty palace, that I may attain the ways and means- The ways and means of (reaching) the heavens, and that I may mount up to the god of Moses: But as far as I am concerned, I think (Moses) is a liar!" [Qur'ân 40:36-37]

Who is Haman? It appears that no commentator of the Qur'ân has dealt with this question on a thorough hieroglyphic basis. As previously mentioned, some authors have suggested that "Haman" is reference to Haman, a counsellor of Ahasuerus who was an enemy of the Jews. While others have been searching for consonances with the name of the Egyptian god "Amun." [33]

Concerning the question of Haman, Dr. Maurice Bucaille says that the best course of action was to ask an expert in Old Egyptian:

The only valid investigation was to ask an expert in Old Egyptian for his opinion about the presence in the Qur'an of this name.[34]

Dr. Maurice Bucaille then narrates an interesting discussion he had with a prominent French Egyptologists:

In the book Reflections on the Qur'an (Réflexions sur le Coran[35]), I have related the result of such a consultation that dates back to a dozen years ago and led me to question a specialist who, in addition, knew well the classical Arabic language. One of the most prominent French Egyptologists, fulfilling these conditions, was kind enough to answer the question.

I showed him the word "Haman" that I had copied exactly like it is written in the Qur'an, and told him that it had been extracted from a sentence of a document dating back to the 7th century AD, the sentence being related to somebody connected with Egyptian history.

He said to me that, in such a case, he would see in this word the transliteration of a hieroglyphic name but, for him, undoubtedly it could not be possible that a written document of the 7th century had contained a hieroglyphic name - unknown until that time - since, in that time, the hieroglyphs had been totally forgotten.

In order to confirm his deduction about the name, he advised me to consult the Dictionary of Personal Names of the New Kingdom by Ranke[36], where I might find the name written in hieroglyphs, as he had written before me, and the transliteration in German.

I discovered all that had been presumed by the expert, and, moreover, I was stupefied to read the profession of Haman: "The Chief of the workers in the stone-quarries," exactly what could be deduced from the Qur'an, though the words of the Pharaoh suggest a master of construction.

When I came again to the expert with a photocopy of the page of the Dictionary concerning "Haman" and showed him one of the pages of the Qur'an where he could read the name, he was speechless...

Moreover, Ranke had noted, as a reference, a book published in 1906 by the Egyptologist Walter Wreszinski[37]: the latter had mentioned that the name of "Haman" had been engraved on a stela kept at the Hof-Museum of Vienna (Austria). Several years later, when I was able to read the profession written in hieroglyphs[38] on the stela, I observed that the determinative[39] joined to the name had emphasised the importance of the intimate of Pharaoh.[40]

And he went on to say:

Had the Bible or any other literary work, composed during a period when the hieroglyphs could still be deciphered, quoted "Haman," the presence in the Qur'an of this word might have not drawn special attention. But, it is a fact that the hieroglyphs had been totally forgotten at the time of the Qur'anic Revelation and that no one could not read them until the 19th century AD. Since matters stood like that in ancient times, the existence of the word "Haman" in the Qur'an suggests a special reflection.[41]

We have now shown that certain non-Muslims scholars and Christian Missionaries have clearly no basis for their allegations, that the Prophet Muhammad(P) mixed Biblical stories and Jewish myths of the Tower of Babel, Esther and Moses into a single confused account when composing the Qur'ân.

These false allegations continue to persist. Unfortunately, you will find this type of methodology being used over-and-over again. We regularly encounter baseless allegations which are used to attack the Qur'ân and the noble character of the Prophet Muhammad. Other documents to be found on this web-site will bear testimony to the false and intellectually dishonest arguments that are sometimes employed against Islâm.

5. Conclusions

In this article we have tried to show the historicity of a few statements made in the Qur'ân concerning ancient Egypt: the role of the Pharaoh in Egyptian society as god, the desire of Pharaoh to ascend to the sky, and the use of bricks in Egyptian construction and the person Haman.

When one compares the data of Egyptology to what is contained in numerous verses of the Qur'ân, one has to admit that there is a remarkable degree of agreement between the two. The Egyptological data quoted above shows that the name Haman is a personal name of the New Kingdom. Although neither the Bible nor the Qur'ân name the Pharaoh, we do know that one of his counsellors was called Haman whose hieroglyphic name has been engraved on a stela kept at the Hof-Museum of Vienna (Austria); the secular data is not precise enough to determine who the Pharaoh was in question.

The historicity of Haman provides yet another death-blow to the theory that parts of the Qur'ân were allegedly copied from the Bible. If hieroglyphs were long dead and the Book of Esther a work of fiction, then from where did the Prophet Muhammad(P) obtain his information? The Qur'ân answers:

Your Companion is neither astray nor being misled. Nor does he say (aught) of (his own) Desire. It is no less than inspiration sent down to him. He was taught by one mighty in Power. [Qur'ân 53:2 - 5]

It is interesting to note that the meaning of the word ayah, usually translated as verse in the Qur'ân, also means a sign and a proof. The reference to Haman and other facts concerning ancient Egypt in the Qur'ân suggests a special reflection.

Now, what if we were to reverse the question concerning Haman and apply it to the Bible?

Haman occurs in the Qur'anic story of Pharaoh and Moses in Egypt, 1,100 years before the story of Esther. Haman is not a Babylonian name but Egyptian. The reference to Haman in the story of Biblical book of Esther is an anachronism.

There is more information that needs to be researched concerning Ancient Egypt in the Qur'ân. We will be updating the information on this website as soon as new information becomes available, inshallah.

And Allah knows best.

{...}

Notes & References

{...}

[33] Sher Mohammad Syed, Historicity Of Haman As Mentioned In The Qur'ân: 1980, The Islamic Quarterly, Volume XXIV, No. 1 & 2, First & Second Quarter, Islamic Cultural Centre, London.

[34] Maurice Bucaille, Moses And Pharaoh: The Hebrews in Egypt: 1995, NTT Mediascope Inc., Tokyo, pp. 192-193.

[35] Mohamed Talbi & Maurice Bucaille, Réflexions sur le Coran: 1989, Seghers, Paris.

[36] Hermann Ranke, Die Ägyptischen Personennamen, , Verzeichnis der Namen, Verlag Von J J Augustin in Glückstadt, Band I (1935), Band II(1952).

[37] Walter Wreszinski, Aegyptische Inschriften aus dem K.K. Hof Museum in Wien: 1906, J C Hinrichs' sche Buchhandlung, Leipzig, I34, pp. 130.

[38] Ranke mentions the name with a reference to Wreszinski's Aegyptische Inschriften. The profession Vorsteher der Steinbruch arbeiter - "The Chief of the workers in the stone-quarries" is also to be found in Wreszinski's book.

[39] Many old Egyptian words are written with the same signs, even if they have a completely different meaning. To permit an understanding of the meaning of words, so-called determinative signs were written at the end of a word, to help determine the word's meaning. Most determinatives serve to indicate the general category of the word they describe. Determinative signs can also assist when translating old Egyptian. The ancient Egyptians had a habit of writing sentences without spaces between words, and without an indication of the start of a new sentence. Because determinative signs are placed at the end of words, they provide a means to decipher the sentence.

[40] Bucaille, Moses And Pharaoh: The Hebrews in Egypt, Op. cit. pp. 192-193.

[41] Ibid.

Version 1.6 |

Historical Errors Of The Qur'ân: Pharaoh & Haman

Elias Karîm, Qasim Iqbal & M S M Saifullah

© Islamic Awareness, All Rights Reserved.

Last Updated: 20th November 2000

Assalamu-alaikum wa rahamatullahi wa barakatuhu:

1. Introduction

Controversy has prevailed since 1698 CE about the historicity (i.e., historical reality or authenticity) of a certain Haman, who according to the Qur'an, was associated with the Court of Pharaoh to whom Moses(P) was sent as a Prophet by Almighty God (Allah):

Pharaoh said: "O Haman! Build me a lofty palace, that I may attain the ways and means- The ways and means of (reaching) the heavens, and that I may mount up to the god of Moses: But as far as I am concerned, I think (Moses) is a liar!" [Qur'an 40:36-37]

Haman is mentioned six times in the Qur'an and is referred to as an intimate person belonging to the close circle of Pharaoh.

Western scholars have concluded that Haman is unknown to Egyptian history. The name Haman is first mentioned in the Biblical book of Esther, some 1,100 years after Pharaoh. The name is said to be Babylonian, not Egyptian. According to the book of Esther, Haman was a counsellor of Ahasuerus (the Biblical name of Xerxes) who as an enemy of the Jews. It has been suggested that Muhammad(P) mixed Biblical stories and Jewish myths of the Tower of Babel, the story of Esther and Moses into a single confused account when composing the Qur'an.

We propose here to examine the various aspects of the controversy in light of recent historical and archaeological discoveries.

{...}

4. Pharaoh and Haman In The Qur'an

Let us now examine the passages in the Qur'an concerning the Pharaoh and Haman in light of recent historical and archaeological discoveries.

{...}

4.3 The Making Of Bricks In Ancient Egypt

In the Qur'an the Pharaoh, who boastful and mocking, asks his associate Haman to build a lofty tower:

Pharaoh said: "O Haman! light me a (kiln to bake bricks) out of clay, and build me a lofty palace (Arabic: Sarhan, lofty tower or palace), that I may mount up to the god of Moses: but as far as I am concerned, I think (Moses) is a liar!" [Qur'an 28:38]

The command of Pharaoh was but a boast, but a new question now arises: Were mud bricks ever burnt (baked) in Egypt at this time? It is a well known fact, borne out by archaeological research, ...

{...}

4.5 The Mystery Of The Name Haman

Haman is mentioned six times in the Qur'an: surah 28, verses 6, 8 and 38; surah 29, verse 39; and surah 40, verses 24 and 36. He was close to Pharaoh who, boastful and mocking, said:

Pharaoh said: "O Chiefs! no god do I know for you but myself: therefore, O Haman! light me a (kiln to bake bricks) out of clay, and build me a lofty palace (Arabic: Sarhan, lofty tower or palace), that I may mount up to the god of Moses: but as far as I am concerned, I think (Moses) is a liar!" [Qur'an 28:38]

"O Haman! Build me a lofty palace (Arabic: Sarhan, lofty tower or palace), that I may attain the ways and means- The ways and means of (reaching) the heavens, and that I may mount up to the god of Moses: But as far as I am concerned, I think (Moses) is a liar!" [Qur'an 40:36-37]

The above ayahs portray Haman as someone close to Pharaoh, who was also in charge of building projects, otherwise the Pharaoh would have directed someone else. So, who is Haman? It appears that no commentator of the Qur'an has dealt with this question on a thorough hieroglyphic basis. As previously mentioned, some authors have suggested that "Haman" is reference to Haman, a counsellor of Ahasuerus who was an enemy of the Jews. While others have been searching for consonances with the name of the Egyptian god "Amun."[35]

Concerning the question of Haman, Dr. Maurice Bucaille believes that the best course of action was to ask an expert in Old Egyptian:

The only valid investigation was to ask an expert in Old Egyptian for his opinion about the presence in the Qur'an of this name.[36]

Dr. Maurice Bucaille then narrates an interesting discussion he had with a prominent French Egyptologists:

In the book Reflections on the Qur'an (Réflexions sur le Coran [37]), I have related the result of such a consultation that dates back to a dozen years ago and led me to question a specialist who, in addition, knew well the classical Arabic language. One of the most prominent French Egyptologists, fulfilling these conditions, was kind enough to answer the question.

I showed him the word "Haman" that I had copied exactly like it is written in the Qur'an, and told him that it had been extracted from a sentence of a document dating back to the 7th century AD, the sentence being related to somebody connected with Egyptian history.

He said to me that, in such a case, he would see in this word the transliteration of a hieroglyphic name but, for him, undoubtedly it could not be possible that a written document of the 7th century had contained a hieroglyphic name - unknown until that time - since, in that time, the hieroglyphs had been totally forgotten.

In order to confirm his deduction about the name, he advised me to consult the Dictionary of Personal Names of the New Kingdom by Ranke,[38] where I might find the name written in hieroglyphs, as he had written before me, and the transliteration in German.

I discovered all that had been presumed by the expert, and, moreover, I was stupefied to read the profession of Haman: "The Chief of the workers in the stone-quarries," exactly what could be deduced from the Qur'an, though the words of the Pharaoh suggest a master of construction.

When I came again to the expert with a photocopy of the page of the Dictionary concerning "Haman" and showed him one of the pages of the Qur'an where he could read the name, he was speechless...

Moreover, Ranke had noted, as a reference, a book published in 1906 by the Egyptologist Walter Wreszinski:[39] the latter had mentioned that the name of "Haman" had been engraved on a stela kept at the Hof-Museum of Vienna (Austria).[40] Several years later, when I was able to read the profession written in hieroglyphs on the stela, I observed that the determinative[41] joined to the name had emphasised the importance of the intimate of Pharaoh.[42]

And he went on to say:

Had the Bible or any other literary work, composed during a period when the hieroglyphs could still be deciphered, quoted "Haman," the presence in the Qur'an of this word might have not drawn special attention. But, it is a fact that the hieroglyphs had been totally forgotten at the time of the Qur'anic Revelation and that no one could not read them until the 19th century AD. Since matters stood like that in ancient times, the existence of the word "Haman" in the Qur'an suggests a special reflection.[43]

It is obvious, therefore, that there is no evidence whatsoever that the appearance of Haman in the Qur'an in a historical period different from that of the Bible involves any confusion with the Biblical version of history as claimed by a number of Orientalists and Christian Missionaries. There is clearly no basis for their allegations, that the Prophet Muhammad(P) mixed Biblical stories and Jewish myths of the Tower of Babel, Esther and Moses(P) into a single confused account when composing the Qur'an.

Such false allegations continue to persist and are widely circulated. Unfortunately, one will find this type of methodology being used over-and-over again. We regularly encounter baseless allegations which are used to attack the Qur'an and the noble character of the Prophet Muhammad(P) . Other documents to be found on this web-site will bear testimony to the false and intellectually dishonest arguments that are sometimes employed against Islam.

5. Conclusions

In this article we have tried to show the historicity of a few statements made in the Qur'an concerning ancient Egypt: the role of the Pharaoh in Egyptian society as god, the desire of Pharaoh to ascend to the sky, and the use of bricks in Egyptian construction and the person Haman.

When one compares the data of Egyptology to what is contained in numerous verses of the Qur'an, one has to admit that there is a remarkable degree of agreement between the two. The Egyptological data quoted above shows that the name Haman is a personal name of the New Kingdom. Although neither the Bible nor the Qur'an name the Pharaoh, we do know that one of his counsellors was called Haman whose hieroglyphic name has been engraved on a stela kept at the Hof-Museum of Vienna (Austria); the secular data is not precise enough to determine who the Pharaoh was in question.[44]

The historicity of Haman provides yet another death-blow to the theory that parts of the Qur'an were allegedly copied from the Bible. If hieroglyphs were long dead and the Book of Esther a work of fiction, then from where did the Prophet Muhammad(P) obtain his information? The Qur'an answers:

Your Companion is neither astray nor being misled. Nor does he say (aught) of (his own) Desire. It is no less than inspiration sent down to him. He was taught by one mighty in Power. [Qur'an 53:2 - 5]

It is interesting to note that the meaning of the word ayah, usually translated as verse in the Qur'an, also means a sign and a proof. The reference to Haman and other facts concerning ancient Egypt in the Qur'an suggests a special reflection.

The fact remains that there is an unhistorical Haman in the book of Esther. This unhistorical Haman is portrayed as the prime minister of Ahasuerus, King of Persia. The plot of the unhistorical Haman to annihilate the Jews in the Persian empire in retaliation to Mordecai's refusal to bow to him, seems to be the corrupt version of the original event when Haman had a hand in suggesting and executing the second massacre of the Israelites newborn males to demoralise the Israelites and discourage them from following Moses:

And indeed We sent Moses with Our ayat (proofs, evidences, verses, lessons, signs, revelation, etc.), and a manifest authority.

To Pharaoh, Haman and Qarun, but they called (him): "A sorcerer, a liar!"

Then, when he brought them the Truth from Us, they said "Kill the sons of those who believe with him and let their women live"; but the plots of the disbelievers are nothing but in vain! [Qur'an 40:23 - 25]

There is more information that needs to be researched concerning Ancient Egypt in the Qur'an. We will be updating the information on this website as soon as new information becomes available, insha'allah.

And Allah knows best.

{...}

Notes & References

{...}

[35] Syed suggests that "Haman" is a title of a person not his name, just as Pharaoh was a title and not a proper personal name. Syed proposes that the title "Haman" referred to the "high priest of Amun". Amun is also known as "Hammon" and both are normal pronounciations of the same name. Syed's identification of Haman as "the high priest of Amun" may be probable. See Sher Mohammad Syed, "Historicity Of Haman As Mentioned In The Qur'an", The Islamic Quarterly: 1980, Volume XXIV, No. 1 and 2, First & Second Quarter, Islamic Cultural Centre, London.

[36] Maurice Bucaille, Moses and Pharaoh: The Hebrews in Egypt: 1995, NTT Mediascope Inc., Tokyo, pp. 192-193.

[37] Mohamed Talbi and Maurice Bucaille, Réflexions sur le Coran: 1989, Seghers, Paris.

[38] Hermann Ranke, Die Ägyptischen Personennamen, Verzeichnis der Namen, Verlag Von J J Augustin in Glückstadt, Band I (1935).

[39] Walter Wreszinski, Aegyptische Inschriften aus dem K.K. Hof Museum in Wien: 1906, J C Hinrichs' sche Buchhandlung, Leipzig.

[40] The name is listed as masculine, from the New Kingdom. The profession translated into German reads Vorsteher der Steinbruch arbeiter - "The Chief/Overseer of the workers in the stone-quarries" (Aegyptische Inschriften, I34, p. 130).

[41] In hieroglyphic writing words are sometimes written with meaning-signs, or determinatives, placed at the end of the word. Determinatives do not contribute to the sounds of the word and so are not transliterated. They simply help us to get some general idea of the meaning of a word. Most determinatives serve to indicate the general category of the word they describe. Determinative signs can also assist when translating old Egyptian. The ancient Egyptians had a habit of writing sentences without spaces between words, and without an indication of the start of a new sentence. Because determinative signs are placed at the end of words, they provide a means to decipher the sentence.

[42] Bucaille, Moses and Pharaoh: The Hebrews in Egypt, Op. cit. pp. 192-193.

[43] Ibid.

[44] It is not possible to determine whether this inscription refers to the Qur'anic Haman. What we do know however is that the name Haman is attested in Ancient Egypt, it is a masculine name, and dates to the New Kingdom period, the period of history in which Moses is associated.

Version 2.2 |

Historical Errors Of The Qur'an: Pharaoh & Haman

M S M Saifullah, Elias Karim, `Abdullah David & Qasim Iqbal

© Islamic Awareness, All Rights Reserved.

First Composed: 20th November 2000

Last Updated: 4th June 2006

Assalamu-`alaykum wa rahamatullahi wa barakatuhu:

1. Introduction

Controversy has prevailed since the late 17th century CE about the historicity of a certain Haman, who according to the Qur'an, was associated with the court of Pharaoh to whom Moses was sent as a Prophet by Almighty God (Allah):

Pharaoh said: "O Haman! Build me a lofty palace, that I may attain the ways and means- The ways and means of (reaching) the heavens, and that I may mount up to the god of Moses: But as far as I am concerned, I think (Moses) is a liar!" [Qur'an 40:36-37]

Haman is mentioned six times in the Qur'an and is referred to as an intimate person belonging to the close circle of Pharaoh.

Many western scholars have concluded that Haman is unknown to Egyptian history. The name Haman is first mentioned in the Biblical book of Esther, some 1,100 years after Pharaoh. The name is said to be Babylonian, not Egyptian. According to the book of Esther, Haman was a counsellor of Ahasuerus (the Biblical name of Xerxes) who was an enemy of the Jews. It has been suggested that Prophet Muhammad mixed Biblical stories, namely the Jewish myths of the Tower of Babel and the story of Esther and Moses into a single confused account when composing the Qur'an.

We propose to examine the various aspects of the controversy in light of recent historical and archaeological discoveries.

{...}

4. Pharaoh & Haman In The Qur'an

Let us now examine the passages in the Qur'an concerning the Pharaoh and Haman in light of recent historical and archaeological discoveries.

{...}

THE MAKING OF BURNT BRICKS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

In the Qur'an, the Pharaoh in a boastful and mocking manner, asks his associate Haman to build a lofty tower:

Pharaoh said: "O Haman! light me a (kiln to bake bricks) out of clay, and build me a lofty palace (Arabic: Sarhan, lofty tower or palace), that I may mount up to the god of Moses: but as far as I am concerned, I think (Moses) is a liar!" [Qur'an 28:38]

The command of Pharaoh was but a boast, but a question now arises: Were Burnt Bricks Used In Ancient Egypt In The Time of Moses?

The use of burnt brick in Egypt did not become common until the Roman Period. However, ...

{...}

Haman is mentioned six times in the Qur'an: Surah 28, verses 6, 8 and 38; Surah 29, verse 39; and Surah 40, verses 24 and 36. The above ayahs portray Haman as someone close to Pharaoh, who was also in charge of building projects, otherwise the Pharaoh would have directed someone else. So, who is Haman? It appears that no commentator of the Qur'an has dealt with this question on a thorough hieroglyphic basis. As previously mentioned, many authors have suggested that "Haman" in the Qur'an is reference to Haman, a counsellor of Ahasuerus who was an enemy of the Jews. Meanwhile others have been searching for consonances with the name of the Egyptian god "Amun."[58]

One of the earliest scholars to deal with the name "Haman" in the Qur'an from the point of view of Egyptology was Dr. Maurice Bucaille. He surmised that since "Haman" was mentioned in the Qur'an during the time of Moses in Egypt, the best course of action was to ask an expert in the old Egyptian language, i.e., hieroglyphs, regarding the name.[59] Bucaille narrates an interesting discussion he had with a prominent French Egyptologist:

In the book Reflections on the Qur'an (Réflexions sur le Coran[60]), I have related the result of such a consultation that dates back to a dozen years ago and led me to question a specialist who, in addition, knew well the classical Arabic language. One of the most prominent French Egyptologists, fulfilling these conditions, was kind enough to answer the question.

I showed him the word "Haman" that I had copied exactly like it is written in the Qur'an, and told him that it had been extracted from a sentence of a document dating back to the 7th century AD, the sentence being related to somebody connected with Egyptian history.

He said to me that, in such a case, he would see in this word the transliteration of a hieroglyphic name but, for him, undoubtedly it could not be possible that a written document of the 7th century had contained a hieroglyphic name - unknown until that time - since, in that time, the hieroglyphs had been totally forgotten.

In order to confirm his deduction about the name, he advised me to consult the Dictionary of Personal Names of the New Kingdom by Ranke, where I might find the name written in hieroglyphs, as he had written before me, and the transliteration in German.

I discovered all that had been presumed by the expert, and, moreover, I was stupefied to read the profession of Haman: "The Chief of the workers in the stone-quarries," exactly what could be deduced from the Qur'an, though the words of the Pharaoh suggest a master of construction.

When I came again to the expert with a photocopy of the page of the Dictionary concerning "Haman" and showed him one of the pages of the Qur'an where he could read the name, he was speechless...

Moreover, Ranke had noted, as a reference, a book published in 1906 by the Egyptologist Walter Wreszinski: the latter had mentioned that the name of "Haman" had been engraved on a stela kept at the Hof-Museum of Vienna (Austria). Several years later, when I was able to read the profession written in hieroglyphs on the stela, I observed that the determinative joined to the name had emphasised the importance of the intimate of Pharaoh.[61]

He went on to say:

Had the Bible or any other literary work, composed during a period when the hieroglyphs could still be deciphered, quoted "Haman," the presence in the Qur'an of this word might have not drawn special attention. But, it is a fact that the hieroglyphs had been totally forgotten at the time of the Qur'anic Revelation and that no one could not read them until the 19th century AD. Since matters stood like that in ancient times, the existence of the word "Haman" in the Qur'an suggests a special reflection.[62]

Let us now cross-check some of the statements made by Bucaille. The following entry tabulated in Walter Wreszinski's Aegyptische Inschriften aus dem K.K. Hof Museum in Wien mentions the name hmn-h, though no critical analysis of the hieroglyph was provided.

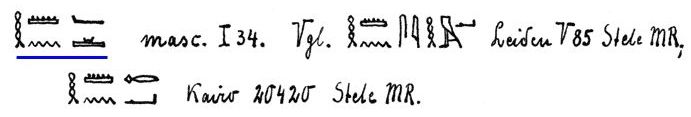

Figure 4: Hieroglyph entry for "hmn-h" and his profession "Vorsteherder Steinbruch arbeiter" meaning "the chief / overseer of the workers in the stone-quarries" and dates from the New Kingdom Period.[63]

Figure 5: More information on "hmn-h". Notice that the "hmn-h" mentioned by Wreszinski is masculine.[64]

While discussing this name, Hermann Ranke in his Die Ägyptischen Personennamen was unsure what the last letter "h" in the name hmn-h represented. Therefore, he designated the entry as "hmn-h(?)" as if suggesting "h" was not actually part of the name.[65]

In order to understand how the hieroglyphs are written and interpreted, let us take a look at the salient features of this form of writing. The Egyptian hieroglyphs are one of the oldest writing systems in the world. In 391 CE when the Byzantine Emperor Theodosius I closed all pagan temples throughout Egypt, it resulted in the termination of a four thousand year old tradition. The message of the ancient Egyptian language was lost for 1500 years and not until the discovery of the Rosetta stone and the work of Jean-Francois Champollion (1790-1832) that the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs awoke from their long slumber as a dead language. The Egyptian hieroglyphic writing consists of an inventory of signs and is divided into three major categories, namely logograms, signs that write out morphemes; phonograms, signs that represent one or more sounds; and determinatives, signs that denote neither morpheme nor sound but help with the meaning of a group of signs that precede them. It is usually a picture of an object which helps the reader to understand the object and the context. The Egyptian hieroglyphs disregard the vowels. In other words, with this system one arrives at words that are connected by vowels. For example, let us take the word "beautiful". Its transcription in the Egyptian hieroglyphics is nfr. To ease the pronunciation of these three consonants, they are bound together with "e-sounds", which leads to nefer.[66] This pronunciation bears no relation with the original pronunciation of the Egyptian language. It is solely a convention to enable communication among the modern scholars or even commonfolk interested in ancient Egyptians hieroglyphs. It is not surprising that the scholarly pronunciation of Egyptian hieroglyphs (even consonants!) also differs.[67]

The hieroglyph in our case is hmn-h(?) with a doubtful last letter. If we drop the last letter which is doubtful, the name can be rendered as "hemen" or "haman" depending upon the vowel which is inserted to ensure an effective pronunciation of the hieroglyph. It is interesting to note that the profession of this person hmn-h(?) in German reads Vorsteherder Steinbruch arbeiter - "The chief / overseer of the workers in the stone-quarries" (Fig. 4) . This name is listed as masculine (Fig. 5) and it is from the New Kingdom Period (Fig. 4). The generally accepted theory appears to be that Moses lived during the reign of kings Rameses II or his successor Merenptah in the New Kingdom Period. The Qur'an suggests that Haman was a master of construction and this name appears to fit very well in almost all respects.

However, an objection can be raised regarding the contents in the hieroglyph and the Qur'an. The Qur'an uses ه (/h/) instead of ح (/h/) for the name "Haman". The hieroglyph from the K.K. Hof Museum in Vienna above uses ح (/h/) instead of ه (/h/) in hmn. This objection can be tackled in two ways. Firstly, when the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs were discovered by Jean-Francois Champollion, it was already a dead language. The phonology of the hieroglyphs were not known and even today, albeit with considerable amount of progress in Egyptian phonology, there remain uncertainties concerning the exact pronunciation of a word in ancient Egyptian. For example, in the case of /h/ and /h/, Carsten Peust says:

It is presently impossible to decide whether the primary distinction of /h/ and /ḥ/ [i.e., /h/] was one of voice or one of place of articulation.[68]

Secondly, in Roman Demotic and contemporary hieroglyphic texts, a graphical confusion arises between /h/ and /h/, suggesting a phonetic merger had taken place. Both sounds conflate into ϩ (i.e., hori) /h/ in all Coptic dialects. It appears that /h/ and /h/ are not distinguished in Arabic loanwords from Coptic.[69] As to how far back this merger in Egyptian history goes back is not very clear. There are early examples of a merger between /h/ and /h/ from the New Kingdom Period mentioned by Jürgen Osing.[70]

The question now arises as to whether the Haman mentioned in the hieroglyph from the K.K. Hof Museum is the Haman mentioned in the Qur'an. Maybe. Although there are a lot of interesting similarities between the Haman's mentioned in the Qur'an and in the hieroglyph, it is currently not possible to determine with a great degree of certainty whether this hieroglyph refers to the Qur'anic Haman. What we do know, however, is that the name Haman is attested in ancient Egypt, it is a masculine name, and it dates to the New Kingdom period, the period of history in which Moses is principally associated.

It is also interesting to note that there also existed a similar sounding name called Hemon[71] (or Hemiunu / Hemionu[72] as he is also known as), a vizier to King Khnum-Khufu who is widely considered to be the architect of Khnum-Khufu's the Great Pyramid at Giza. He lived in the 4th Dynasty of the Old Kingdom Period (c. 2700 - 2190 BCE).

(a)

![]()

(b)

Figure 6: (a) Statue of Hemon, Khufu's master builder. The eyes have been hacked out by robbers, and restored.[73] This statue is in the Hildesheim Museum. (b) The hieroglyph showing the name "Hemiunu".[74]

He is said to have been buried in a large and splendid tomb at Saqqara in the royal necropolis. There is an extant statue of Hemiunu / Hemon, which resides in the Hildesheim Museum [Fig. 6(a)]. Although the name Hemiunu / Hemon is quite similar to Haman, they are written differently [compare the hieroglyphs in Fig. 6(b) with Fig. (4)] and perhaps also pronounced differently. The writing of Hemiunu employs Gardiner signs U36 O28. This is different from what we have seen for hmn which employs V28 Y5 N35.

5. Conclusions

Marraccio's identification of the Qur'anic Haman as having been appropriated from the Hebrew Bible and Jewish mythology was subsequently adopted by Protestant scholars and missionaries. Adam Clarke's assessment of Marraccio's translation indicates that the Protestants unabashedly adopted this Roman Catholic pronouncement. One must note with a sense of alarm the ability of this 'critical note' to endure for over 300 years without anyone seemingly taking the opportunity to evaluate the veracity of Marraccio's untested assumptions. Concerning the name Haman, such illustrious entries in the Encyclopaedia Of Islam and the Encyclopaedia Of The Qur'an make no attempt to engage with the Egyptological historical record.

Marraccio's assumption of the historicity and authenticity of the biblical narrative has been shown by contemporary Judaeo-Christian scholars to be misplaced. As we have observed, that the book of Esther lacks historicity is not too unexpected. This unhistorical Haman is portrayed as the prime minister of Ahasuerus, King of Persia. The plot of the unhistorical Haman to annihilate the Jews in the Persian Empire in retaliation for Mordecai's refusal to bow to him, seems to be the corrupt version of the original event when Haman had a hand in suggesting and executing the second massacre of the Israelites newborn males, to demoralise the Israelites and discourage them from following Moses. Athanasius whose famous Epistola Festalis of 367 CE settled the limits of the New Testament canon at the twenty-seven books accepted as canonical by Protestants today, unceremoniously rejected Esther from his exclusive list of 'divinely-inspired' Old Testament books. Even the Jews had difficulty deciding on the canonicity of Esther.

Wreszinski's Aegyptische Inschriften aus dem K.K. Hof Museum in Wien published in 1906 CE noted a hieroglyph engraved on a stela kept at the K.K. Hof Museum in Vienna, Austria, contained the letters hmn-h. About thirty years later while discussing this name, Ranke in his Die Ägyptischen Personennamen was unsure what the last letter "h" in the name hmn-h represented. Therefore, he designated the entry as "hmn-h(?)" suggesting as if "h" was not in actuality part of the name. If we drop the doubtful last letter, the name can be rendered as "hemen" or "haman" depending upon the vowel which is inserted to ensure an effective pronunciation of the hieroglyph. It is interesting to note that the profession of this person hmn-h(?) in German reads Vorsteherder Steinbruch arbeiter - "The chief / overseer of the workers in the stone-quarries" (Fig. 4). This name is listed as masculine (Fig. 5) and it is from the New Kingdom Period (Fig. 4). The generally accepted theory appears to be that Moses lived during the reign of King Rameses II or his successor Merenptah in the New Kingdom Period. The Qur'an suggests that Haman was a master of construction and this name appears to fit very well in almost all respects. However, it is unclear whether Haman mentioned in the hieroglyphs is actually the Hamam mentioned in the Qur'an. More research would throw some light on this issue.

The historicity of the name Haman provides yet another sharp reminder to those that adhere to the precarious theory that parts of the Qur'an were allegedly copied from the Bible. If Egyptian hieroglyphs were long dead and the Book of Esther a work of fiction, then from where did the Prophet Muhammad obtain his information? The Qur'an answers:

Your Companion is neither astray nor being misled. Nor does he say (aught) of (his own) desire. It is no less than inspiration sent down to him. He was taught by one mighty in Power. [Qur'an 53:2-5]

It is interesting to note that the meaning of the word ayah, usually translated as 'verse' in the Qur'an, also means a sign and a proof. The reference to Haman and other facts concerning ancient Egypt in the Qur'an suggests a special reflection.

And Allah knows best!

References & Notes

{...}

[58] Syed suggests that "Haman" is a title of a person not his name, just as Pharaoh was a title and not a proper personal name. Syed proposes that the title "Haman" referred to the "high priest of Amun". Amun is also known as "Hammon" and both are normal pronunciations of the same name. Syed's identification of Haman as "the high priest of Amun" may be probable. See S. M. Syed, "Historicity Of Haman As Mentioned In The Qur'an", The Islamic Quarterly, 1980, Volume 24, No. 1 and 2, pp. 52-53; Also see a slightly modified article by him published four years later: S. M. Syed, "Haman In The Light Of The Qur'an", Hamdard Islamicus, 1984, Volume 7, No. 4, pp. 86-87.

[59] M. Bucaille, Moses and Pharaoh: The Hebrews In Egypt, 1995, NTT Mediascope Inc.: Tokyo, p. 192.

[60] M. Talbi and M. Bucaille, Réflexions sur le Coran, 1989, Seghers: Paris.

[61] M. Bucaille, Moses and Pharaoh: The Hebrews In Egypt, 1995, op. cit. pp. 192-193.

[62] ibid.

[63] W. Wreszinski, Aegyptische Inschriften aus dem K.K. Hof Museum in Wien, 1906, J. C. Hinrichs' sche Buchhandlung: Leipzig, I 34, p. 130.

[64] ibid., p. 196.

[65] H. Ranke, Die Ägyptischen Personennamen, 1935, Volume I (Verzeichnis der Namen), Verlag Von J. J. Augustin in Glückstadt, p. 240.

[66] C. Peust, Egyptian Phonology: An Introduction To The Phonology Of A Dead Language, 1999, Monographien Zur Ägyptischen Sprache: Band 2, Peust & Gutschmidt Verlag GbR mit Haftungsbeschränkung: Göttingen, pp. 54-55.

[67] ibid., pp. 52-53.

[68] ibid., p. 98.

[69] ibid., p. 99 and Appendix 8 on p. 323.

[70] J. Osing, Die Nominalbildung Des Ägyptischen: Anmerkungen Und Indices, 1976, Deutsches Archäologisches Institut: Abteilung Kairo, Verlag Philipp von Zabern: Mainz / Rhein, Note 47, pp. 367-368.

[71] P. A. Clayton, Chronicle Of The Pharaohs: The Reign-By-Reign Record of The Rulers And Dynasties Of Ancient Egypt, 1994, Thames and Hudson: London, p. 47.

[72] "Hemionu" in M. Rice, Who's Who In Ancient Egypt, 1999, Routledge: London and New York, p. 63.

[73] The restored statue was compared with fragments of relief of Hemiunu. For this interesting study see G. Steindorff, "Ein Reliefbildnis Des Prinzen Hemiun", Zeitschrift Für Ägyptische Sprache Und Altertumskunde, 1937, Volume 70, pp. 120-121.

[74] H. Junker, Giza I. Bericht über die von der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wein auf Gemeinsame Kosten mit Dr. Wilhelm Pelizaeus unternommenen. Grabungen auf dem Friedhof des Alten Reiches bei den Pyramiden von Giza, 1929, Volume I (Die Mastabas der IV. Dynastie auf dem Westfriedhof), Holder-Pichler-Tempsky A.-G.: Wein and Leipzig, pp. 132-162 for the complete description of Hemon's mastaba. The name and title of Hemon are discussed in pp. 148-151. For the hieroglyphs inscribed at the footstool of the statue of Hemon representing the titles see Plate XXIII; For a good discussion of reliefs of Hemon / Hemiunu, see W. S. Smith, "The Origin Of Some Unidentified Old Kingdom Reliefs", American Journal Of Archaeology, 1942, Volume 46, pp. 520-530.